story | message | visualizations

[and the taste of things to come]

Is the story, in experience design strategy —

a segmented telling — each, to their own.

What is the taste of the experiencer?

I was working in NYC, and I was talking with a friend [client] about micro-segmentation of messaging, positioning, brand and spend allocations.

Knowing the big picture, the larger core message and positioning, then filtering that to layers of community and relationships, is about layered expressions — all of them resonate to the foundation the core ring of “what we stand for,” and how we tell it — and the spreading of touch points that are specific to every member of the community, to each, their own. But, tuned — that tiering.

I was talking to some friends [in the trade] about this idea — and we were tossing out models for how to explain it, and I thought that the positioning of food, ingredients, spice and flavoring made for a good and obvious allegory. Everyone gets that. Everybody eats — but what they eat, and how to feed them is the challenge.

Thinking about the tailoring of product, spend, experience design or retail strategy, there is one category we’re all studying — the proverbially “disloyal” Millie. [The Millennial] — how do we get them to like us, to believe in us — trust us?

Food, as a story, is so foundational to a humanity and ethnographic index — that, working on food brands, restaurant design, strategy and innovation, food — I find the crossovers to other categories from food branding, packaging, presentation, retail design experience — to be relevant. You can take that to motion picture work, fashion, department and specialty store marketing and architecture. Food, to sustenance, has a foundation.

Scan the notations below and let me know what you think.

Tim | Girvin NYC

The Strategy of Holism | Restaurant Experience Design

TouchPoints, Storytelling and Guest Engagement

How America Eats Today

Fast, Fresh, Flavorful: Marketers Are Adapting to the New Demands of a Rapidly Changing Food World

Published: November 11, 2012

If we are what we eat, then America is more complex than ever.

We are so obsessed with on-the-go food that even a bowl of cereal is seen as a hassle for some, and the last thing we want to do is turn on an appliance. But as we seek convenience, we also crave complexity, looking for the same bursts of flavors in a bag of chips as we get at a fine restaurant. We want variety. The average number of items sold at a supermarket has ballooned to more 38,000 today from 10,425 in 1977, according to the Food Marketing Institute, which includes some non-food items. Yet at the same time, an increasing number of us are demanding simplicity, prompting brands to trim ingredient lists or promote products as “natural,” gluten-free or both.

Add it up, and it gets pretty confusing for marketers, who can count on one thing only: They can no longer appeal to a mass market of consumers who once reliably shopped for the same items at the same places.

In many cases, the forces shaping the food world are driven by consumer groups with rapidly diverging tastes. Consider the well-to-do food elitists practicing what shopper-marketing firm SAI Marketing calls “food one-upsmanship,” living a “post-acquisitive” lifestyle in which food experiences — rather than jewelry or sports cars—are emerging as the primary luxury purchase. Yet the majority of us are “food realists” who simply looking to get by as we seek more deals from familiar brands.

Moreover, the two biggest food-buying generations are asserting their wills, often in conflicting ways. Millennials are disloyal, shopping anywhere, anytime and in constant search of variety and new ethnic foods, often from smaller brands. To them, yesterday’s chop suey is today’s “sofrito,” a trendy mix of Latin herbs, vegetables and spices.

Baby boomers, meanwhile, still have favorite brands, but their behaviors are also changing. They seek smaller package sizes as they age and have fewer mouths to feed.

As a result, “established food brands and traditional grocery stores will be pressured at both ends by sets of consumers with very different value equations,” according to investment bank Jefferies Group and AlixPartners, a global-business advisory firm, which recently published a joint report called “Trouble in Aisle 5.” The changes “appear poised to rapidly transform the food-at-home industry, long thought of as a bastion of stability.”

For marketers, change is not coming. It is already here, forcing them to find new ways to innovate, advertise and distribute.

But in this new era, the giant food companies have lost some of the upper hand to retailers, which are armed with more consumer data thanks to loyalty cards, said Lynn Dornblaser, director-innovation and insight for market research group Mintel. Also, internet-enabled consumers can jump en masse on to the latest trends often before large companies can launch products. Consider the Greek-yogurt craze, initially fueled by startups such as Fage and Chobani, which blossomed because of word-of-mouth buzz, and it had barely any traditional marketing.

“There’s so much more [big CPGs] go up against now than they did 20 years ago,” Ms. Dornblaser said.

Here is how the industry is responding to five key trends:

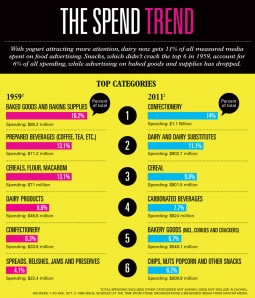

Convenience, Redefined

“New Convenience Items Balloon Food Sales,” stated an Ad Age headline in 1960. What was all the excitement about? Frozen meals, cake mixes and instant potatoes — foods that by today’s standards would be considered a bit of a hassle. We are now living in a yogurt-and-snack-bar world, where the fastest-growing foods are those that often require little or no preparation. “We’re looking for how to make life easier,” said Harry Balzer, an analyst with NPD Group, which follows food trends. “We don’t want to change the amount of time we spend eating. We want to change the amount of time before and after.”

Indeed, of the 10 fastest-growing in-home foods and beverage categories over the past decade, only two are routinely heated (pizza and pasta), while the rest are pretty much open-and-eat, such as nuts and chips, according to NPD. Even staples such as soup and cereal — once considered easy — have lost momentum to items that can be scarfed down on the go.

Brands are putting old products in new, convenient forms. For instance, Kellogg Co. this year launched Eggo Wafflers, which are flavored tear-apart waffle bars meant to be eaten right out of the toaster — no syrup needed. J&J Snack Foods Corp. has managed to squeeze hashed-brown potatoes, eggs, cheese green peppers and onions into rolled form for a grab-and-go product called Tater Stuffers that are making their debut on the roller grill at convenience stores. No utensils required.

Meanwhile, advertising plays up portability, such as Fiber One’s recent “snackcessory” contest, which asked consumers to design their own case to hold their “delicious snacks.” And Heinz has plugged its dip-and-squeeze ketchup packs with an online video showing a man deftly applying the condiment to a burger while driving and on a work conference call. “A new day has dawned for those whose sustenance must be swift,” bellows a voice-over.

‘Elites’ and ‘Realists’ Replace

the Middle Market

“We’ve had a melting away of the middle market,” said Bill Melnick, senior director-strategic planning for SAI Marketing. SAI defines “food elites” as those making more than $100,000 a year who demand natural and handmade foods. For them, what they eat forms “a core part of their self-perception.” And they obsessively consume food media, such as Saveur magazine, whose recent Halloween entertaining guide encouraged people to choose foods like deviled eggs with pickled jalapenos — not exactly a Snickers bar — over store-bought stuff.

At the other end is 84% of the population, which SAI dubs “food realists.” For these value-seeking consumers, authenticity does not mean knowing exactly where all the ingredients are from, but buying brands that “signify familiarity,” according to SAI.

Nusara Chinnaphasaen, VP-senior brand planner at ad agency Cramer-Krasselt, went so far as to describe food as a “battlefield.” Food has become “such a mark of our social status and it really has divided people more than ever before,” she said. There is even a growing backlash against the foodies led by so-called anti-foodies — those tired of worshipping food, she said.

All of this means companies are trying to offer the same brands at different price points and in different formats to appeal to these fragmenting consumer groups. Kraft Foods Group is trying what it calls a “good, better, best” approach. For instance, it offers Velveeta Shells “n Cheese in a cup for 99 cents, in a box for $1.99 and in Cheesy Skillet dinner kits for $3.49. The company is plugging economy brands — such as Kraft string cheese — at dollar stores, while pouring more advertising into premium products. For instance, its Cracker Barrel cheese brand just launched its first campaign in more than a decade with ads that spotlight awards it has won at prestigious cheese competitions.

To keep pace with the food elites, companies are paying closer attention to the fine-dining scene. Leo Burnett and Kellogg formed a joint food culture study group called Marinate that recently heard from Stephanie Izard, executive chef of Chicago’s popular Girl and the Goat restaurant. People “live outside” the package-foods category, said Megan Van Someren, Leo Burnett Worldwide’s global head of planning for Kellogg. They are influenced by films, shows and restaurants “and that’s what is setting their expectations” at the grocery store, she said.

Meanwhile, in further evidence to the food-as-lifestyle trend, Bon Appétit magazine has broadened its focus to more cultural coverage of restaurants, travel, home entertaining and more from purely epicurean. It is also luring more ads from non-food brands in the beauty and fashion world, said VP-Publisher Pamela Drucker Mann. “As a foodie myself, to me it was a no-brainer that food is lifestyle,” she said. “That epicurean sensibility just seemed a little outdated. Consumer mind-sets have changed.”

Catering to ‘Unloyal’ Millennials

Meet the “Yemmie,” the young educated, millennial mother that the Jefferies/Alix report says will largely set the tone for the generation. For big brands and retailers, she is a potential nightmare — less loyal than her mother and demanding of variety and foods that are natural but also convenient. Millennial eating habits are scattered. Sometimes they eat snacks for breakfast, breakfast for dinner and dinner as a midnight snack, according to Cramer-Krasselt’s Ms. Chinnaphasaen. Boomers are a lot more predictable and loyal. But their influence is waning, with annual food-at-home spending declining as much as $15 billion a year through 2020, compared with a yearly $50 billion increase for millennials, according to Jefferies/Alix.

With millennials, “you can’t just hedge and try to add a dash of hipness to traditional marketing,” said David Garfield, a managing director at Alix. So old-school companies are designing products from scratch just for millennials. Campbell Soup Co. is out with a “Go Soup” brand in microwavable pouches with exotic flavors like Moroccan Style Chicken with Chickpeas. PepsiCo’s Frito-Lay now sells a bevy of exotic and ethnic snack flavors, including Doritos Jacked, which comes in flavors such as smoky chipotle barbecue, and Doritos Dinamita, a chile-limon flavored chip in rolled form. At the same time, Frito-Lay targets older consumers with its more sophisticated Tostitos “artisan” lineup, which it tested at Costco. “The marketplace is segmenting. We have more [items] than we’ve ever had before,” said Christine Kalvenes, Frito-Lay’s VP-innovation. “But we also have more channels of distribution.”

It’s What’s Inside That Counts

“Low-in” claims, such as those promoting sodium reduction, used to be the rage. Now “it’s more about talking about the presence of positives as opposed to the absence of negatives,” said Mintel’s Ms. Dornblaser. “Consumers are looking for products that make it easy for them to understand what’s good about [tjhem]. That can be communicated in a lot of ways. It could be [the] small number of ingredients, it could be talking about the fruit and vegetable content or talking about the grain content or talking about the protein content.” And lately for new products, the word of choice is “natural” rather than “organic,” she said, partly because “organic equals expensive, and so that is a negative for some consumers.” And while “low-in” claims are out, gluten-free is still hot.

Kellogg has a campaign called “start simple, start right” that touts core cereals such as Raisin Bran as being made with “seven ingredients or less.” Lay’s potato chips promote “three simple ingredients” (potatoes, oil, salt). Yoplait yogurt just launched Simplait, which touts “just 6 simple ingredients.” Haagen-Dazs markets an ice-cream brand called “Five” (with five ingredients).

General Mills is creating more gluten-free versions of brands and has launched a one-stop shop website called Gluten Freely, which also includes gluten-free offerings from other marketers. Smart Balance is renaming itself Boulder Brands and creating a division named “Natural” as it seeks a larger presence in natural foods and to grow existing brands such as plant-based Earth Balance and gluten-free Glutino and Udi’s. Part of the transformation includes moving the company headquarters to Boulder, Colo., which CEO Steve Hughes calls the “Silicon Valley of natural foods.” He said: “I don’t think people trust what is in the mainstream food chain. I think there is a lot of concern out there.” Still, there remains plenty of demand for fatty, processed foods.

Small Is Getting Bigger

While big brands and companies might control most of the market share, smaller brands are gaining. Consider the rise of specialty foods, whose sales grew 9.2% from 2009 to last year, reaching $75.14 billion, according to the National Association for the Specialty Food Trade, which is the trade organization for foods that are premium, made by small manufacturers or have ethnic or exotic flavors. And consider the craft-beer industry, which now controls about 9% of all beer sales measured by dollars, according to the Brewers Association, thanks to hundreds of regional, full-flavored brews.

That’s caused big companies to put more energy into smaller, separately branded divisions in an attempt to look small. MillerCoors launched a division called Tenth & Blake to focus on craft beers. Kellogg continues to invest in Kashi, its natural-foods division run out of Southern California, far from the company’s Michigan headquarters. “You’re going to see us continue to launch more Kashi cereals, more Kashi bars,” said Kellogg North America President Brad Davidson. “Kashi will be for the Kellogg company our pioneering health brand.”

Just how far has the American palate come in the last half-century? Sixty years ago when the specialty food trade organization launched, Swiss chocolate was considered exotic and the standard ethnic food options were Italian pasta and chop suey. This year the organization highlighted something called “local-global” as a hot trend at its summer fancy-food show, spotlighting a brand named Chulita’s Famous, a Latin seasonings company based in Brooklyn that specializes in sofritos.

One can only wonder what the next 60 years will bring.

Copyright © 1992-2012 Crain Communications | Privacy Statement | Contact Us