Studying the world of Brian Eno: scent, strategy, music and environment in experience design and contemplation.

Image Copyright, Apple Computer, Inc., © 2008, all rights reserved.

“Humans are capable of a unique trick: creating realities by first imagining them, by experiencing them in their minds. When Martin Luther King said “I have a dream…” , he was inviting others to dream it with him. Once a dream becomes shared in that way, current reality gets measured against it and then modified towards it. As soon as we sense the possibility of a more desirable world, we begin behaving differently – as though that world is starting to come into existence, as though, in our minds at least, we’re already there. The dream becomes an invisible force which pulls us forward. By this process it starts to come true. The act of imagining something makes it real.”

Brian Eno — from the Board messages | The Long Now.

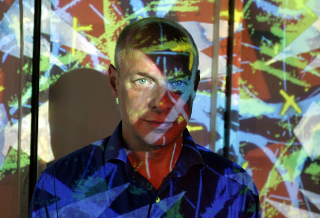

What I’m curious about, actually, is the mind of Eno. And how music, scent, thinking and philosophy seem to come together in the mind-full amalgam of his creativity over the course of the last 60 years.

I’d written, some time back (http://blog.girvin.com/nice-one-eno) about the 77 Million Paintings (http://www.longnow.org/77m/) digital piece that Apple had featured on his work. And I’d been wondering about that project: what that means to thinking about creating a digitally populated, self-generating field for art.

But there’s a lot to Eno that’s about virally infected ideas — things that start with some little sampled bit, then rove to infections of larger vectors, creating whole new ways of thinking. And listening. And sensing.

77 Million does that — there are an opening group of “odes”, these “songs” translate out to millions of interpretations.

I suppose that the opening epiphany for me was really about the concept of ambient music, which was, back then, the 70s, such a wildly quirky (yet cool) gesture to sound-in-space. Music for Airports, ambient creation one — www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQ3b_s0f7lg — was such a surprising opening — even the title was ambigious. I mean, really, who listens to sound in airports? Even today, music in airports is not ambient-based — it’s a long sprinkling of ridiculous Homelandian messages — enough, I’d surmise, to drive an airport worker “postal”.

There are few ambient “tinctures” that are attractive — with exception to the sound implications of the long, subsurface corridor beneath the various United terminals at O’Hare. LaGuardia, in the late 80s, actually used Eno’s Music for Airports, for a brief stint.

But what I find intriguing is the idea of experience | and experiment | in sound — to be a curious balance in the mind of Eno, that is, as well, about his fascination with scent.

His love there is seemingly heady with emotion:

“And I love it: I love watching us all become dilettante perfume blenders, poking inquisitive fingers through a great library of ingredients and seeing which combinations make sense for us, gathering experience – the possibility of better guesses – without certainty.” (the best scent / Eno link up is here: http://music.hyperreal.org/)

Physically, scent mixes in the air. How it’s experienced by one person, is different in sentient access, than another. Same with sound. Sound influences people differently. There are, I imagine, tonal expectations — people hear something and they are turned up, turned in — or tuned down and out. But there are nuances, just like in scent, that are subtle. They are either attracted, distanced, emotionally disconnected, or repelled. What is interesting is considering the idea between scent and music, ambience and experience design. To the concept of how this might be reliably defined, I believe there is no measure — even to Eno — about the concept of sound, or scent, in mapping music or scents, as noted in this blog capture [as per Taking Vetiver by Strategy: Brian Eno on Perfume | July 22, 2006. ]:

“You don’t have to dabble for very long to begin to realize that the world of smell has no reliable maps, no single language, no comprehensible metaphorical structure within which we might comprehend it and navigate our way around it.”

Of course, I can relate. The scent space that I live in is vetiver-based — very dirty, smoke, leather, woods — so the opening allegory to that foundation speaks to my heart. But the idea of creating scent maps is the contrary position to Eno’s curiosity about randomness and generative music — what I mean is that he is, on the one hand, fascinated by the concepts of music that are “self looping,” virally induced or based on algorithmic expansions — but on the other hand, he tries to quantify it, somehow.

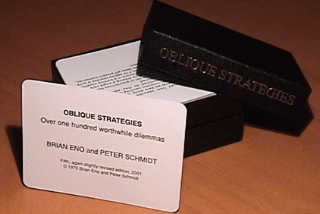

His Oblique Strategies, a series of cards that are designed to create answers to questions, or questions that answer, is an interesting counterbalance to both of these opposites.

In an interview, there’s a query that walks around the connections between music, scent and space. The two banter:

John Alderman: “They’ve started putting it in the water, you know. Why will the future be like perfume?

Brian Eno: That’s a long story. That is a 2 1/4 hour lecture. (Brian likes these — long talks and dissertations on abstract ideas.)

John Alderman: Do you have a favorite perfume?

Brian Eno: At the moment?

John Alderman: Old standbys?

Brian Eno: No, there’s nothing new that I particularly like. I like Guerlain…. I mix my own, you know, and then throw them away. I’ve made a very good sexual perfume, actually.

John Alderman: Did you have a title for it? What’s it like?

Brian Eno: I can’t tell you that, this is not an ironic enough country to give you the full title of it. You’d like it.”

Hmm… In connecting personally, and live, with Brian, either in the early 80s in Vancouver, or later in Seattle, I never linked to his scent explorations — at least directly by smell. Actually, when I met him, I didn’t know of his interests.

But he’s that — in direct experience: vague, yet genial — which is kind of how I’d experienced him in those encounters, that is, friendly, quiet, and vague. Or smoky. Like perfume. And in a manner, this is part of the character of his music (some of it, to be sure): it drifts around you like filmy incense, wandering around your mind, persistently uncovering recollection and tangential content — the archaeology of memories, associating and re-minding.

In this grouping of review of experiments between Robert Fripp (and his guitar “frippertronics“), there’s something to this concept of vaporous splay. I think about the idea of music and scent in the context of artifacts — things that are left over in the mind and, perhaps, newly rediscovered:

From Dusted Magazine:

“Long-time followers of Fripp and Eno will notice artifacts typical of each artist’s work from the represented eras: the looped space-jazz dub of Eno’s Nerve Net and The Drop; the fuzzed-out ostinatos of solo guitar Frippertronics; bass and drum with swirling improv redolent of Fripp’s various King Crimson spin-off Projects. Eno works his usual magic with effects and textures: filters, delays, metallically resonant and constantly morphing synth tones.

Since, however, the sort of treatments that Eno once pioneered have become an expected and even everyday part of pop and rock production now, it might well be the form and architecture of these pieces that remains more radical to current perceptions. Eno is an avowed dabbler in the art of making perfume, and floating, drifting constructions like “Dirt Loop” and “Voices” are unique in the way they seem to occupy an ambiguity between physicality and memory similar to that of scent.”

And in an added allegory, Chris Richards, in a special missive (How Brian Eno Helped Travelers Check Their Emotional Baggage | 8 / 2 /2007) in the Washington Post recalls the link between sound and “fumes”:

“four slices of sublime sonic vapor make up Eno’s now-legendary “Ambient 1: Music for Airports,” an album that taught an entire generation of musicians to consider music as a texture. Eno’s name might be fuzzy, but you know his work…more ubiquitous than those musicians’: He’s the guy who composed that cascading trill for Microsoft back in the ’90s — the one you hear when you turn on your PC.”

I find the descriptions of music, between scent and the sequencing of the “acquisition of notesn” and the melodic phrasing to how we hear, to be an added deepening of the connection between the idea of experience in fragrance (like Eno’s Neroli — both scent and story — attached to, and built around, music) and the sensing of sound. “The pieces, disparate in mood and texture as they might be, are sequenced artfully.In its variously tinted and constant flow of juxtapositions, the overall effect of Beyond Even is satisfyingly similar to that of Eno’s classic Music For Films releases,” Kevin Macneil Brown notes from the Dusted Magazine article (above).

Sounds like smell, to me.

And there is inspiration in scenting — Eno, intriguingly, finds his “hits” in the air: “Eno, musical scientist, in which he is circling the notion that he sniffs out new music.

“If I am close to something new, I can smell it in the air, and even though whatever it is doesn’t stay in the same place and it changes form as time goes on, I know when I’m close to it because I can smell it in the air. Sometimes the smell is a bit faint and it’s buried under a lot of other things. But if I give myself time I can find it again.” (Paul Morley | 2001)

He goes on: “He thinks of a neglected part of his art and design work from over the years. “Well, there’s the perfume. I put a lot of time into perfume, and nothing really came of that apart from the lecture.” The lecture he gave about perfume eight years ago, which also involved a talk about David Bowie‘s wedding, and other things, was his last “live” performance, if you don’t count installation works in museums around the world and bike rides around his neighbourhood.

I mention that I’m surprised that there isn’t an Eno perfume available at airport duty-free shops, called “Discreet”, or “Perfume For Wearing”.

“Well, actually, as you were saying that, I’ve just thought of another way of writing my name. En’Eau.”

I’d buy it. It would smell like his new record, Drawn From Life. Smell like a moment in time, with a phantom suggestion of late Miles, and a cryptic nod and a near-wink to Schoenberg and DJ Shadow and Common and Jan Garbarek and Fila Brazilia and Meredith Monk. Mostly, it would smell of Eno.”

Paul Morley continues to walk the openng stride of Eno’s scented creativity — his under-nourished, as he’d put it, intelligent explorations:

“A knowing, known and unknown smell that’s as pleasant as you want, and light and dark, and nothing else. Enophiles will recognise it if they’re familiar with the odour of Evening Star, the ardour of Before And After Science, the colour of My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts, the dissolved edge of Low, and the pallor of The Drop.

They’ll know the float, the beat, the curve and the way an image of sound reflects itself in the mirror of time. What’s new is the fact that all that Eno has learnt about space and rhythm and tempo and illusion and peace and noise is moved together in one vast, intimate location. So, yes, it smells like Eno but an Eno who has just stepped out of the shower in a hotel room in the nearest city to a jungle, or a desert, or a frozen wasteland, or a far-fetched coast. The music is as modern and as poignant as your next breath. And within that as tentatively, tense as a breathless moment.”

Eno himself offers this distinctive “distillation” of his own philosophical “rendering” in Frieze magazine’s Perfume, Defence and Davis Bowie’s Wedding, a rather famous art talk, performance at a packed presentation at Sadler Wells:

“a cheerful ironist, a fundamentalism doubting ‘non-rootist’, and a willing participant in a chancy future in which there will be no ‘hard distinctions’ and even moral concepts like ‘freedom’ and ‘justice’ will be up for grabs – tell that to Bosnian Muslims. ‘I’m waiting,’ he claimed, for everything else to become like perfume.”

Of course, what does that mean? It’s all about smoke and dissolution — scented one moment, dissolved in vapor, another instant.

There’s a great poetic phrasing by Zen explorer and haiku composer, Basho, that reminds me about this whole discussion — at least to imagery and impression:

“The temple bell stops ringing, but the sound keeps coming out of the flowers.”

And, this is — in a way — what it is about: the momentary experience, what is sensed, then recalled — and the evanescence of that encounter. Scent, like music, fades, the beauty of the instant can dissipate — but can be, as well — unforgettable.

The opening notes of “Music for Airports“, or the initial scent note phrasing of Guerlain’s Vetiver — I’ll not forget them.

Ever.

tsg

—-

Firenze | Italia