The concept of cult, culture and brand | spirit integrated.

“I have a dream

to devote major portions

of my busy life

to poor community.”

Ratan Tata

I’ve spoken about the concept of the cult of the brand, and the tribes that follow it. And others have followed it, too, with their observations.

I’ve wondered, too, about the concept of brand, as a warming fire, a hearth of sharing and community — and a kind of tribal connection to the love of enterprise. People either are connected to brand, or they are not; they’re either linked in, to embrace — or it’s merely yet another distraction in the multitude of complications that we all face, every day. Love in. Love, out. But in this instance, in speaking with a friend that’s working in India — and for TATA — I’ve learned more about the character of that civilization, and the implications of the spirituality — and how they might be linked.

TATA, as you might know, is unexpectedly one of the biggest, fastest growing groups in the world — internationally flourishing — yet dynamically committed to sharing its resources and people, as a mission — not merely a concomitant attachment to percentage profit diversions — but instead, this sense of contribution being a driver for action, above and beyond everything else. Even in the construct of such amazing new thinking, in the strategy of its organization, it’s a 140 year old brand.

My friend’s role is exploring those links, from brand, to operations, to human resources, and the connective glue that melds them all together. Gary Jusela is a friend, colleague in the trade of brand development, and a client, as well. You can learn more about his work, at the links above. But he’d mentioned something about the brand culture of TATA that sent me off on this exploration. He referenced the profound “spiritual character of the brand” — this being nearly the basis for everything they think about, in the embodiment of the brand. And it’s a sizeable enterprise to comprehend.

Site overviews offer that “Tata is a rapidly growing business group based in India with significant international operations. Revenues in 2007-08 are estimated at $62.5 billion (around Rs251,543 crore), of which 61 per cent is from business outside India. The Group employs around 350,000 people worldwide. The Tata name has been respected in India for 140 years for its adherence to strong values and business ethics.” And rather than focusing on one category of business channel, they embrace many: “the business operations of the Tata Group currently encompass seven business sectors: communications and information technology, engineering, materials, services, energy, consumer products and chemicals. The Group’s 27 publicly listed enterprises have a combined market capitalisation of some $60 billion, among the highest among Indian business houses, and a shareholder base of 3.2 million. The major companies in the Group include Tata Steel, Tata Motors, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), Tata Power, Tata Chemicals, Tata Tea, Indian Hotels and Tata Communications.”

Big. So what about culture — how is that managed and expressed?

The etymology of brand culture

First, my take on brand culture is more to the cultic underpinnings of the word. Cult, culture, cultivation — and finally, colony. They align — and they surely align with the story as well.

cultivate

1620, from M.L. cultivatus, pp. of cultivare, from L.L. cultivus “tilled,” from L. cultus. Figurative sense of “improve by training or education” is from 1681.

cult

1617, “worship,” also “a particular form of worship,” from Fr. culte, from L. cultus “care, cultivation, worship,” originally “tended, cultivated,” pp. of colere “to till” (see colony). Rare after 17c.; revived mid-19c. with reference to ancient or primitive rituals. Meaning “devotion to a person or thing” is from 1829.

culture

1440, “the tilling of land,” from L. cultura, from pp. stem of colere “tend, guard, cultivate, till” (see cult). The figurative sense of “cultivation through education” is first attested 1510. Meaning “the intellectual side of civilization” is from 1805; that of “collective customs and achievements of a people” is from 1867. Slang culture vulture is from 1947. Culture shock first recorded 1940.

colony

c.1384, “ancient Roman settlement outside Italy,” from L. colonia “settled land, farm, landed estate,” from colonus “husbandman, tenant farmer, settler in new land,” from colere “to inhabit, cultivate, frequent, practice, tend, guard, respect,” from PIE base *kwel- “move around” (source of L. -cola “inhabitant;” see cycle). Also used by the Romans to translate Gk. apoikia “people from home.” Modern application dates from 1548. Colonize is from 1622; colonial first recorded 1776, coined by British statesman Edmund Burke (1729-97). Colonialism first attested 1886.

I think about them, based on the etymon. That is, of course, where the truth lies. Looking back, there are broader senses of threading that can be meaningful in reflection — and these are: tilling, worship, tending, people from home. What this means to me is the notion of a “colony” being collectively cared for, nurtured — tilled, or cultivated.

Brand culture, defined by Wikipedia is “a company culture in which employees “live” to brand values, to solve problems and make decisions internally, and deliver a branded customer experience externally. It is the desired outcome of an internal branding, internal brand alignment or employee engagement effort that elevates beyond communications and training.” VentureRepublic extends that meaning to “Strong brands are managed by organisations characterized by their strong internal brand cultures. A strong brand culture is determined by the internal attitudes towards branding, management behaviour and practices of an organisation. These combined efforts are crucial to build and maintain strong brand equity through competitive advantages from branding. The most prominent person to lead these efforts is the CEO and the senior management team.”

TATA delivers on that front, with comprehensive overviews on what they are doing, internationally, to contribute to the communities in which they reside. The detailing of their community work is lengthy, “The many companies of Tata are involved in a wide variety of community development projects and programmes, principally in India but also, increasingly, in different parts of the world (these initiatives are distinct, and separated, from the social uplift efforts of the Tata trusts). The community development endeavours of Tata companies cover many areas, from health and education to livelihoods, women-children welfare and more.” Their “rainbow effect” suggests a “panoply of community development endeavours undertaken by Tata companies — embracing everything from health and education to art, sport and more — has touched, and changed, many lives.”

There is a story here: “The time was the early 1990s and the occasion was gathering of industrialists called by India’s prime minister, PV Narasimha Rao. Representing the Tata group were Chairman Ratan Tata and JJ Irani, the managing director of Tata Steel at that point. “The prime minister proposed that we business people set aside 1 per cent of our net profit for community development projects totally unconnected to the workers and industry any of us was involved with,” recalls Mr Irani. “Mr Tata and I looked at each other; we didn’t make any comment. Later, we drew up a chart that quantified Tata Steel’s contribution on Mr Rao’s scale. We discovered that, over a 10-year period, the company had been dedicating between 3 and 20 per cent of its profits to social development causes. In the years since, depending on profit margins, the figure has continued to vacillate within this band.”

That strategy isn’t something that is merely linked to the Tata Steel group alone, it is not an anomaly for a single Tata company. If there is one attribute common to every Tata enterprise, it has to be the time, effort and resources each of them devotes to the wide spectrum of initiatives that come under the canopy of community development. The money numbers are staggering: by a rough estimate the Tata group as a whole, through its trusts and its companies, spends about 30 per cent of its profits after tax (PAT) on social-uplift programs.

Brand culture and principle

The Tata culture in this critical segment of the overall corporate sustainability matrix — inclusive of working for the benefit of the communities in which they operate, of building India’s capabilities in science and technology, of supporting art and sport — springs from an ingrained sense of giving back to society. According to the leadership refrains of Mr. Irani, “This is a matter of principle for us, it is in our bloodstream,”and it isn’t something we like to shout about. Some people consider social responsibility as an additional cost; we don’t. We see it as part of an essential cost of business, as much as land, power, raw materials and employees.”

The Tata tradition in community development has, since the earliest days of the group’s history, been defined by its core values. It never was charity for its own sake or, as group founder Jamsetji Tata put it, “patchwork philanthropy”. Sustainability, says Kishor Chaukar, a member of the Tata Group Corporate Centre, is of fundamental importance. “I don’t believe charity (alone) makes a substantial impact on society,” he explains. “All you are doing, then, is satisfying the mendicant mentality. The real contribution comes when communities are enabled in a manner that has a sustained developmental impact. That way you empower people, educate them, give them instruments of income, a feeling of self-respect and dignity, a reason to live.”

Admirable positions for one of the largest corporate groups in the world. Tata Steel, Tata Tea and Tata Chemicals, have in-house organisations dedicated to the community development task, but that does not mean smaller companies lag behind. “Each Tata company has its own priorities in social development,” says Mr Chaukar. “They take up whatever is relevant to the communities and constituencies in which they function. Somebody is working in water management, somebody is in education, someone is in Aids containment, someone in income generation; the range is huge. You have to take on board different desires, anxieties, and requirements.”

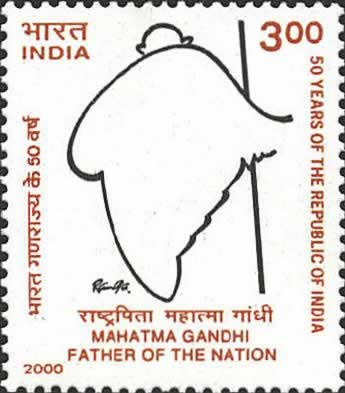

And I wonder where it comes from. To the opening imagery, I ponder if this sensibility might be based on ancient characters of spirituality, or perhaps more particularly, and recently, on the principles of Gandhi. Dr. Devendra Prasad Pandey, Director of the Rajiv Gandhi P.G. College, Allahabad, India offers that alignment, the concept of trusteeship. “Gandhiji advocated trusteeship doctrine all through his life. It is based on the principle that all people having money or property hold it in trust for society. Society is to be regarded as a donor to the individual and accordingly the latter is required to share part of his acquired wealth with the society for mutual benefit. According to this doctrine business organizations have to be viewed as socio-economic institutions to be run and owned by ‘Trust Corporation’ with considerably diluted shareholdings. Most of the ideas of Mahatma Gandhi on trusteeship find expression in his speeches, short notes, and press interviews and informal discussions.”

A reference to that effect: “My idea of society is that while we are born equal, meaning thereby that we all have a right to equal opportunity, all have not the some capacity. It is in the nature of things impossible. For instance, all cannot have same height, colour or degree of intelligence. Therefore, in nature of things, some will have ability to earn more and others less. Normally, people with talents will have more. Such people should be viewed to exist as trustees and in no other terms.”

Still further, reaching thousands of years to the past, to the legacy of the classical text of the Bhagvat Gita

the messaging holds true, from several hundred years before the common era. Gandhi-ji’s doctrine of trusteeship and concept of corporate social responsibilities find expression in following hymns of the Bhagvat Gita.

Javata Priyate Dehuh Tavatsatva Hidehinam/

Adhikam yo bhibhanayat sa stano Dand marhati//

As much as is necessary for one’s own living only that much one entitled to have. One who has excess of this is a thief and deserves punishment.

Ishtan bhogan hi wo deva dasyante yagna bhavitah/

Tairdattan pradaryabhyo yo bhangyakte sten aiv sah//

Fostered by sacrifice (hard work) you will get all enjoyments. He who enjoys it without sacrifice and giving in return is undoubtedly a thief.

Na twaham kamep rajyam na swarnam na puparbhavam/

Kamaye dukh taptanam praninamarti nashwam//

Neither I desire Kingdom nor do I crave for heaven or salvation, I simply desire the end of miseries of all creatures who are afflicted with grief.

Corporate leadership today seeks a positive image, one which pictures business as part of the total society. Business houses seek to demonstrate not only their efficiency, but also their humanism, their social awareness, and their response to national problems. And I suppose that the notion of being truthful — authentic within, and similarly — reflectively — being truth full without is that balancing notion.

As management guru Peter Drucker says: “A healthy society requires three vital sectors: a public sector of effective governments; a private sector of effective businesses; and a social sector of effective community organisations.” While there’s not much it can do about the first sector, the Tata group is contributing all it can to the other two. As a measure, of what I’m doing during these challenging times, the utile question is:

Am I, personally, doing enough? Surely. Not.

tsg

—-

E x p l o r i n g b r a n d + s t o r y + w e l l n e s s :

https://www.girvin.com/new/wellness.php

*The stamp image was provided to me by Stuart Balcomb — as well, an inspiration.

An overviiew on TATA: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tata_Group

Serving communities and contributing to society is to be learnt from Tatas, very nicely presented