The string, in storyline and experience: Jack Larsen, Pat & Dale Keller and Khuan Chew

Interesting, the networks. And how, in connecting, the listening, the community — it reaches out and reaches in. One meeting, means another, if you’re paying attention.

Just reckon, personally, someplace exquisite that you’ve been to — and what drives the marveling of that encounter? The view from a distance, entrance, the corridors, the lighting, the expanse, the view, the materials? The touch of warming wood, the scent of burning stove, the hearing of waterfalls, the taste of tea — what holds you there? It is all of those components, and more. But, in my early exposures to Jack, in talking about his art explorations and adventuring around the globe, his design work, his weaving and fabric/fiber artful legacies — his books, the things that he’s seen, the friends, artists and community he has shared and developed, I admire the profound richness of his life, visioning and wanders — creatively. There are others, surely, that have been out there, gathering cultural references, and building whole collections on those gatherings; but there are few that have done that — and designed on, and with, them — but Jack Lenor Larsen.

The man has a gifted eye, that has persevered generations of comings and goings in the design community. I see him, now and again — and explore what’s next, in the linear light of his curiosity. While he has an apartment in NYC, with increasing frequency, he’s at Longhouse Reserve. And I meet him in both places. Interestingly, in my early NYC years, as a young designer stalking the streets of the city, I met with him during different runs to show my portfolio, to remain connected. I watched the evolution of his work, during that time. And what Jack designs, he lives. And designing amazing objects for interiors, of course, links him — and then me — to others.

So, from Jack, I came to know others. Dale Chihuly, for one. But that relationship was really tangential to Larsen. I took Maddy (my daughter) to a firing, at the (Chihuly) Buffalo Studios, in the earlier glass-making facilities; and there she, and I, met the one-eyed monster. Metaphorically, probably more Hephaestean, or Vulcan, than anything — his visage. But the encounter was powerful, profound, mystical — and there he was — firing out the roaring furnaces with the sensually heated, liquid lava glass — and the wild curly hair, looking up at Madeleine, when she was in her pre-teen “out, exploring with Dad” years. But someone else, that he introduced me to? The legends of Pat and Dale Keller. Among the early pioneers of hospitality and luxuriously entertaining interiors and experiences, they were the first, at the helm — from Seattle, then Hong Kong, London and other pivotal design points of the world — the leaders in extraordinarily (orientally-inspired) hyper-cool places to be on the map.

Grand hotels, palaces, lodges and apartments — they were, the Kellers, at the head of the table, the toast of the design milieu, in terms of sophisticated positioning — and for a time, among the 10 ten interior design / architecture groups for resort and hospitality work in the world. There were surely other mega-firms, big enterprise hotel architecture and interiors groups — but then the real magic lay in the experience — and married expertise — of this couple. Many other talents, nurtured at their shop, spawned from their genetic design offerings. Edward Tuttle — and his evocations for the Aman Resort Group for example — he picked up where the Kellers moved along to retirement — in London, then in Seattle, comfortably ensconced in Bellevue, Washington, in an apartment of their own design. So, I’ve been spending time with them, gathering stories, listening. I come from that age — the very edge of it. For when I was working in the 70s, and 80s, the idea of interior designers, architects and others — uprooted and roving — working on other luxury and exotic locations was relatively commonplace. Designers were out there, on the fringes, designing and creating magic in amazing places and doing captivating work. Back then, as now, I seek them out.

So this story is about strings — and threads that continuously reach to me, and to others, in the spinning of the tale. And one of them recently, emerged, yet again. Khuan Chew. And the connection to Khuan Chew is the Kellers. Khuan worked for seven years for them. She offers, as well: “Dale and Pat – I owe a lot to them for where I am today”.

How this lineage makes sense, is being in Dubai, connecting with the marketing and brand leadership at Jumeirah — and seeing the structure from afar.

After the meeting, and walking the properties of their seaside grouping of hospitality offerings, they’d suggested that I try to make it down to the centerpoint of Jumeirah holdings, the Burj Al Arab. This is the fulcrum of the Al Madinat area. It is quite exquisite, a long-running , shoreside sequence of resort and living destinations, as well as entertainment and shopping complexes; and some of the more comprehensively well-made places that are out there in the Dubai market. I’ve commented elsewhere on some of the sentiments about the spirit of place in Dubai, the sense of vacuity that can emerge in walking the walk of trying to sense levels of experience.

Being there with them, I had to explore the icon of Jumeirah, the Burj Al Arab. And the interiors of which were designed by Khuan Chew. But it’s worth talking about the building, first in clarifying the extension of the story, as well. Building first, then Chew’s work.

The Burj Al Arab (Arabic: برج العرب, “Tower of the Arabs”) is perhaps one of the superlative, luxury overlaid on luxury hotels in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, built by Said Khalil; it was designed by Tom Wright, Atkins, London.

At 321 metres (1,053 ft), it was the tallest building used exclusively as a hotel — that, just recently, changed: the Rose Tower, also in Dubai, has already topped Burj Al Arab’s height, in April 2008. The Burj Al Arab stands on an artificial island 280 metres (919 ft) out from Jumeirah beach, it is connected to the mainland by a private curving bridge. It is an iconic structure, designed to symbolize Dubai’s urban transformation and to mimic the sail of a boat — the classical Arabian sailing vessel, the dhow.

Construction of Burj Al Arab began in 1994, it was constructed to image the sail, as well as two “wings” spread in a V to form a vast “mast”, while the space between them is enclosed in a massive atrium. Atkins architect has commented –Tom Wright: “The client wanted a building that would become an iconic or symbolic statement for Dubai; this is very similar to Sydney with its Opera House, or Paris with the Eiffel Tower. It needed to be a building that would become synonymous with the name of the country.” This design strategy was enabled by the Atkins team — architect and engineering consultant, the UK’s largest multidisciplinary design group, constructed by South African construction contractor Murray & Roberts. It cost $650 million to build.

According to Atkins overview — the engineering required forms of stabilization that were never before designed: several features of the hotel required complex engineering feats to achieve.

For example, the hotel rests on an artificial island constructed 280 meters offshore — to integrate the foundation, the builders drove 230 40-meter long concrete piles into the sand. The foundation is then held in place not by bedrock, but by the friction of the sand and silt along the length of the piles. Additionally, the engineers created a surface layer of large rocks, which is circled with a concrete honey-comb pattern, which serves to protect the foundation from erosion. It took three years to reclaim the land from the sea, but less than three years to construct the building itself. In the final assembly, the building contains over 70,000 cubic meters of concrete and 9,000 tons of steel. To the interiors, other engineering and temperature challenges emerged. Inside the building, the atrium is 180 meters (590 ft) tall.

During the construction phase, to lower the interior temperature, the building was cooled by one degree per day over 6 months. This was to prevent large amounts of “condensation or in fact even a rain cloud from forming in the hotel during the period of construction.” This task was accomplished by several cold air nozzles, which point down from the top of the ceiling, and blast a 1 meter cold air pocket down the inside of the sail. This creates a buffer zone, which controls the interior temperature without massive energy costs.

Burj Al Arab characterizes itself as the world’s only “7-star” property, a designation considered by travel professionals to be hyperbole. It is the world’s tallest structure with a membrane façade and the world’s tallest hotel (not including buildings with mixed use) and was the first 5-star hotel to surpass 1,000 ft (305 m) in height. Although it is characterized as the world’s only 7-Star Hotel, several other “7 Star” hotels have also entered the market. The Flower of the East under construction in Kish, Iran, The Centaurus Complex under construction in Islamabad, Pakistan and a complex planned for Metro Manila in the Philippines, the Pentominium in Dubai, the Morgan Complex, Beijing.

The building design comprises a steel exoskeleton wrapped around a reinforced concrete tower. The splayed dhow structuring, spreads in two “wings” spread in a V to form a vast “mast”.

The space between the wings is sheathed by a Teflon-coated fiberglass sail, curving across the front of the building and creating an atrium inside — made of Dyneon, spanning over 161,000 square feet (15,000 m

This treatment consists of two layers, and is divided into twelve panels and installed vertically. The fabric is coated with DuPont Teflon to protect it from harsh desert heat, wind, and dirt; as a result, “the fabricators estimate that it will hold up for up to 50 years.”

The character of the interior armature, mixed with the external sail structuring, is a remarkable geometric framework, inventively engineered — balanced against the spirit of other curvillinear rhythms.

This geometric symphony finds itself shaped elsewhere.

With daylight, the white fabric allows a soft, milky light inside the hotel. At night, both inside and outside, the fabric is lit by colored light beams and a shifting dynamic of every-changing lights.

Near the top of the building is a suspended helipad supported by a cantilever. The helipad has featured some of the hotel’s notable publicity events. Irish singer Ronan Keating shot his music video “Iris” on the helipad.

In March 2004, professional golfer Tiger Woods hit several golf balls from the helipad into the Persian Gulf, while in February 2005, professional tennis players Roger Federer and Andre Agassi played an unranked game on the helipad, which was temporarily converted into a grass tennis court, at a height of 211 meters.

Back to the interiors. And Khuan Chew, Design Principal of KCA International. And, of course, the link in relationships — the story unfolds. Other projects by Khuan Chew include the Sultan of Brunei’s palace, Dubai International Airport, Jumeirah Beach Resort Development and the Madinat Resort.

As I was told, her original visioning was white. On white. Somehow, things didn’t quite work out like that. Instead of quiet discipline, the interiors are a riot of color, patterning and wild applications of gold leaf.

More, on understatement, here:

floor, furniture detailing…

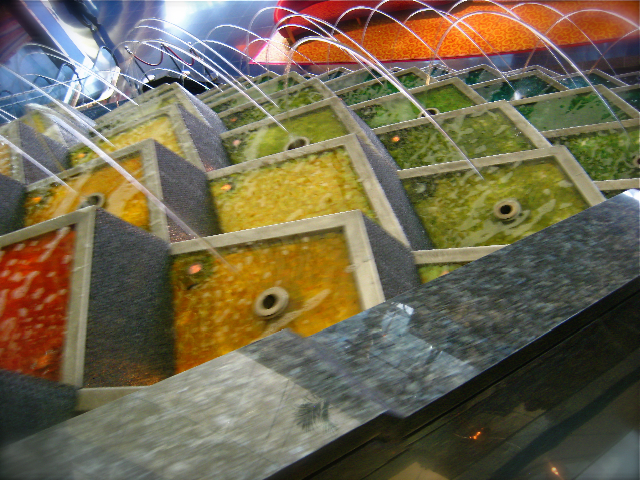

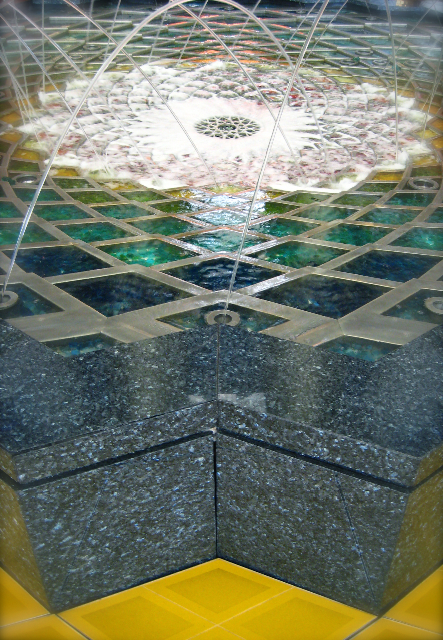

colored glass fountains in marbled geometry…

foyer entry, past gilded columns, to the lobby

conference dining complex

elevator entry details…

foyer chandelier, with the x-strut lobby armature beyond…

entry to the hotel with gilded ceiling coving…

shell for reception…

palette of the atrium ribbing…

restaurant entry treatments…

geometric floor fountain

Second floor lobby…

floor mosaic treatments

These, frankly, are mere gestures, there’s far more to consider in the range of the complexity of Chew’s work — and it’s all over the top, crazy luxury. It celebrates luxury, the lust for more. And more. And, well, more. But, in the wildest shores of the work, there’s a commitment there — a passion to do that, carry it off, even as extraordinarily eccentric as the framing might be seen, in scene. That’s what I’m grateful for. In the string of connections — one, Jack Larsen, then Chihuly, Tuttle, the Kellers, and now — in studying the work, it’s about passion. Every person I’m inspired by, lives there.

I live there.

Passion to do something extraordinary, in the making of….

tsg | jumeirah | dubai

—-

Exploring architecture and experience design:

https://www.girvin.com/subsites/humanbrands/

Other references:

Our work for Jumeirah:

https://www.girvin.com/blog/154-south-gate-at-the-jumeirah-essex-house-nyc/

Jumeirah:

http://www.jumeirah.com/en/hotels-and-resorts/Destinations/Dubai/Burj-Al-Arab/

The rooms at Burj Al Arab:

Overview:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burj_Al_Arab

Icon — the sail.

http://www.eikongraphia.com/?p=91