The idea of place, community and the acculturation of coolness.

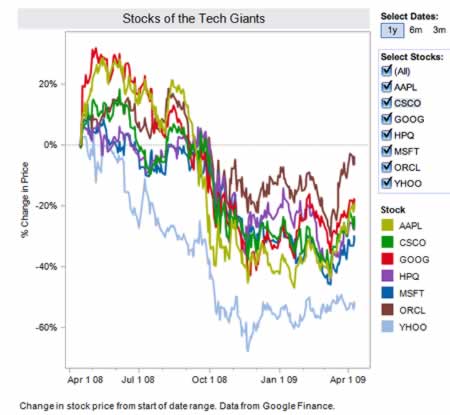

What about that, the idea of opening with a chart that’s about the crashing of the tech stocks? Well, in a way, that’s a two fold gesture, one’s here, to our friends at Tableau and their new tools for the visualization of data, and the other is about the character of brand coolness and the relationship to trend and emergence. Tech is that place.

But there’s more. I’d written earlier, about the idea of cool— that space of the hip, the trendy, the evanescent moment that so many try to hold on to. I’m cool, you’re cool; and they’re cool — at least for now. Hot, too.

It’s hard to be cool (or hot) for a long time. And geographic shifting of what’s cool, what is the hippest place to be in, is a good evocation of speed in culture. Things change, and fast. And during this time of continuous upheaval, the very notion of cool is one of constant migration. Tough for brands, or people, that are trying to be cool, with the exception of some.

I contemplate the notion of place, and cool, and the intertwining of them. How does one place become cooler than another? Other people have been thinking about this — perhaps not specifically to the notation of the coolest places made, but the idea of an environment creating an acculturation, an accumulation, a magnetizing — an attractant that suggests coolness — a hip conclave of action, intelligence, artful exploration, theatrical vitality and literary energy; it’s alive. Every city has them — an agglomeration of engaging places of cultural energy.

They come, they last for a bit, they go. They age. While Soho, NYC might’ve been the coolest place in the city, a decade ago; the Meatpacking District might soon be another, Nolita, another; Brooklyn, Bronx, Harlem — and finally, while other areas pop and merge and twinkle, then peter out — to newly arriving destinations of hip.

But there are people that study hipness — or trend. And what is that — the move:

trend(v.)

1598, “to run or bend in a certain direction” (of rivers, coasts, etc.), from M.E. trenden “to roll about, turn, revolve,” from O.E. trendan, from P.Gmc. *trandijanan (cf. O.E. trinde “round lump, ball,” O.Fris. trind, M.L.G. trint “round,” M.L.G. trent “ring, boundary,” Du. trent “circumference,” Dan. trind “round”); origin and connections outside Gmc. uncertain.

I find the spherical connection here intriguing — that trend is more about a circle, than a rolling curve; and that really relates to the construct of place. People gather. Round.

There are other reflections, as well: “have a general tendency” (used of events, opinions, etc.) is first recorded 1863, from the nautical sense. The noun meaning “the way something bends” (coastline, mountain range, etc.) is recorded from 1777; sense of “general tendency” is from 1884. Trend-setter first attested 1960; trendy is from 1962.”, so quotes an etymological dictionary.

In exploring that idea of trend in the spin of brand, design and the storytelling that is evinced in the action of new discovering, I reached to Robyn Waters, a friend.

She slides through trends with the liquidity of a magician. And it’s something that she’s been doing for a long time — decades, actually. According to her description, by Fast Company, as a Master of Design, Linda Tishchler offers, “any garden-variety cool-hunter can spot a hot trend in Milan. But it takes a sleuth with the aesthetic antennae of a Diana Vreeland and the populist heart of a Michael Moore to translate that concept into something that works for soccer moms in Cincinnati.

For 10 years, Robyn Waters did just that for Target Corp., the Minneapolis-based retailer that pioneered the idea that low prices and good design weren’t oxymoronic.”

She left to form her own consulting firm, RW Trend LLC, in 2002, after serving as the retailing giant’s vice president of trend, design, and product development. Robyn was the driving force, ensuring that Target’s product mix was as on trend and as invigoratingly fresh as the wares in retailing’s tonier precincts.

A startling innovation back in the early 1990s, when discount-industry executives presumed that less-affluent customers were content to wait a year for knockoffs of the products sold at higher end retailers. The CEO (now Chairman) of Target, Robert Ulrich, flipped that positioning, putting design at the core of the company’s differentiation strategy. Rather than simply picking and choosing from what was available in the marketplace, as its competitors did, Target developed its own brands, assuring that customers discovered on the shelves was different–more stylish, more current, visibly well designed — and sexier than what they were finding at Kmart and Wal-Mart.

According to Waters, “I’ve always been a believer that a trend for the sake of a trend is not what Target is about.” Rather, to her leadership, the company’s genius lies in its skill at translating inspiration into execution: collaborating with its stable of design talent to deliver products that enhance the lives of customers. And while she’s moved on to evolve her consulting practice, as a sparkling international star and author of trend-study, during her watch, the retailer became a place where both suburban families and young hipsters could find products that were functional, affordable, and beautiful, from trendy, St. Tropez-styled dresses to a Starck-designed product.

Starck’s Target Sippy Cup

Back then, the strategy worked — and continues… With 2008 revenue of $64 billion, Target has grown past competitors Kmart and Sears, and is now second only to Wal-Mart among general merchandisers.

According to Robyn’s overview, the positioning is: “that the trend in trends is that there isn’t one. For every trend these days, there seems to be an equal and opposite reaction.” For everything that’s cool, the inverse, of course, is that this uplift creates downdraft in another. One’s up, the other’s down. Robyn’s dictum to transitioning: “it’s not about what’s next, it’s about what’s important.”

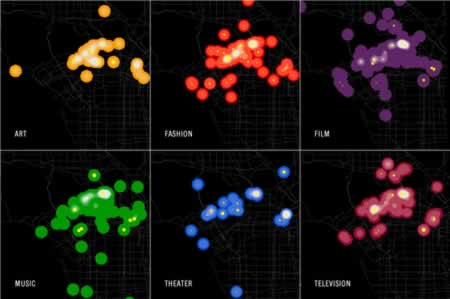

That other trend, to exploration of the transitions of buzz, and hipness in place-making, can be found in the work of Sarah Williams, (and many others, of course — that map and chart the course of cool). Sarah’s a demographic navigator, who’s really doing just that: mapping the cool. As the Director of the Spatial Information Design Lab at Columbia, her research focuses on the presentation of digital information, mapping, ecological design and planning. Before Columbia, she worked at MIT, leading the origination of the GIS Lab, Geographic Information Systems. The work here, lead her to evolve the mapping that she’s created — exploring, in particular, buzz modeling in NYC and Los Angeles.

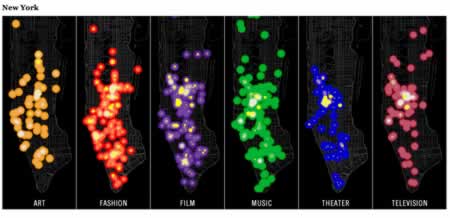

Her research was presented in late March at the annual meeting of the Association of American Geographers. And the character of the study locates hot spots based on the frequency and draw of cultural happenings: film and television screenings, concerts, fashion shows, gallery and theater openings. The trendiest areas in New York are around Lincoln and Rockefeller Centers, and down Broadway from Times Square into SoHo. In Los Angeles the cool stuff happens in Beverly Hills and Hollywood, along the Sunset Strip, as opposed to trendy Silver Lake or Echo Park.

According to writer Melena Ryzik’s review in the NYTimes, Elizabeth Currid describes the aim of the study, called “The Geography of Buzz — was to be able to quantify and understand, visually and spatially, how this creative cultural scene really worked.”

“To do that, Ms. Currid, an assistant professor in the School of Policy, Planning and Development at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, and her co-author, Sarah Williams, the director of the Spatial Information Design Lab at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation; together, they “mined thousands of photographs from Getty Images that chronicled flashy parties and smaller affairs on both coasts for a year, beginning in March 2006.”

Los Angeles hot zones.

Ms., Ryzik notes, “it was not a culturally comprehensive data set, the researchers admit, but a wide-ranging one. And because the photos were for sale, they had to be of events that people found inherently interesting, “a good proxy for ‘buzz-worthy’ social contexts,” they write. You had to be there, but where exactly was there? And why was it there?”

The returning answers were both obvious and not, “a Möbius strip connecting infrastructure (Broadway shows need Broadway theaters, after all), media (photographers need to cover Broadway openings) and the bandwagon nature of popular culture. Buzz, as marketers eagerly attest, feeds on itself, even, apparently, at the building level. A related exhibition opens on Tuesday at Studio-X in the West Village, just south of Houston Street, an area not quite buzzy enough to rank.”

This study is a follow on to the work of Richard Florida — who Currid defines as a mentor — emphasized the importance of the creative class to civic development.

New York

“We had social scientists, economists, geographers all talk about it being so important,” Ms. Currid said. “It matters in the fashion industry, it matters in high tech. The places that produce these cultural innovations matter — the concept of a “branded place”, that is hip, that drives creative confluence; it’s cool, but what, ultimately, is meant by that?

Ms. Currid began focusing on assessing social scenes when doing research and writing her 2007 book, “The Warhol Economy: How Fashion, Art & Music Drive New York City.”

The formulation for the buzz project, comprised the gathering of snapshots from more than 6,000 events — 300,000 photos in all — each of which was categorized according to event type. These selections were controlled for overtly celebrity-powered parties and geo-tagged at the street level, an unusually detailed drilling down, Ms. Williams said. (Socioeconomic data typically follow ZIP codes or broad census tracts.)

Clusters emerged — and they linked to celebrated locations: the Kodak Theater, where the Oscars are held, for example, or Times Square. “Certain places do become iconic, and they become the branded spaces to do that stuff,” Ms. Currid said. “It’s hard to start a new opera house or a new theater district if you already have a Carnegie Hall or a Lincoln Center.” There is some overflow — a rippling out, from the geographic hip-spots. “Why wouldn’t they want to be near the places that already were the places to be?” she asked. “It makes a lot of economic and social sense.”

In a way, the idea of trend, in place, is about the confluence — the flow — in community. People get to a place that’s alive, and they flow. And the ideas flow — art, events, parties, cultural fluidity emerge. But, it’s never permanent except in the context of environments that have some legacy, as Currid notes in the presence of prime brand processions — like Carnegie, Kodak, and others. They act as magnets.

That the buzzy locales weren’t associated with the artistic underground was a quirk of the data set — there were not enough events in Brooklyn to be statistically significant — and of timing. But, in a way, the concept of the quirkier buzz of the artistic milieu, might be considered the seed; the artists move in because a locale might be untouched, remote, inexpensive — and that heritage builds out, others are attracted — and the rhythm grows.

That, in a way, is how buzz happens, getting back to Water’s pronouncements — trend happens, it begins, it moves, it transits; and moves on. But, as well, it’s about rippling — the layering of an opening, that forms another, and now spreads. Another becomes. I find the fact of culture, place and media — in this notion of clustering — to be an interesting compulsion — and while I like to savor places that are proverbially hip — I relish the outer ring of locales that are not; I like emergent hot zones.

“If we took a snapshot two years from now, the Lower East Side would become a much larger place in how we understand New York,” Ms. Currid said.

There is a cycle — cultural events happen, the media is there, imagery is documented, a vibrational “ringing” happens — it circles out there…

The data helped show the continued dominance of the mainstream news media — as the key documentarian — as a cultural gatekeeper. And, in the end, the movement of the trend, the buzz, the hip — it simply keeps going on — and the never-ending cycle of buzz in the creative world.

The trend is that it’s about change, to Robyn’s dictums — in that everything changes, perpetually. But moreso, to importance. What, in trend, is relevant? Buzz in, buzz out. But for the installed icons of cultural gatherings, it’s a cycle of moves that continues to pulsate in one geographic area – and, if vital, will stay that way; other new geographic buzz zones will emerge — flicker and vibrate, perhaps establish themselves and stay activated. Others, like trend — are lesser important and will fizzle. I like to watch those emergences — and, to the conclusions of Elizabeth Currid and Sarah Williams, it can all be reviewed, here.

Is coolness a place, or an attribute of mind?

tsg

—-

E x p l o r i n g b r a n d + s t o r y + c o o l s t u f f :

https://tim.girvin.com/welcome.htm

References:

Buzzspots:

The Standard | NYC: Meatpacking District (a buzz)