What is the nature of the design of camouflage?

Who designs it, and how does it work?

The French cruiser Gloire

A colleague of mine, pointed out an intriguing effort to abstractly camouflage boats during WWI with elaborate geometric rippling, reflective patterning. Amazing, really — that got me thinking about the design of camouflage, what patterning really “hides” something. What are the principles of camou design? And the designers — camoufleurs.

Dazzlement.

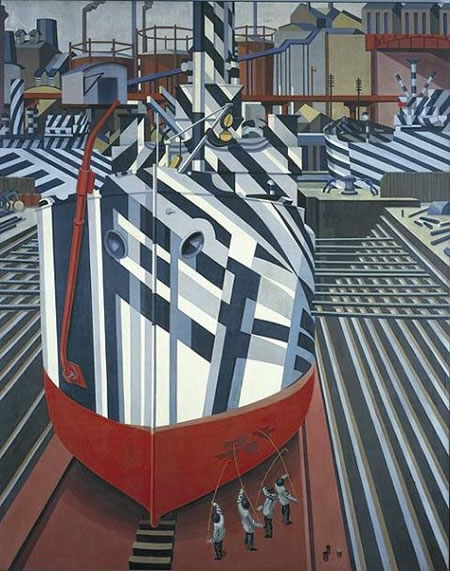

The painting “Dazzle-ships in Drydock at Liverpool” 1919, by Edward Wadsworth

The opening was this phrasing — dazzle painting. Digging around the notion, I found this overview — to not only the idea of dazzle — but camouflage to be an opening to understanding what concealment.

1917, from Fr. camoufler, Parisian slang, “to disguise,” from It. camuffare “to disguise,” perhaps a contraction ofcapo muffare “to muffle the head.” Probably altered by Fr. camouflet “puff of smoke,” on the notion of “blow smoke in someone’s face.” The British navy in World War I called it dazzle-painting.

1915, as a form of military camouflage, from smoke (n.1); 1926 in the fig. sense. The association of smoke with “deception, deliberate obscurity” dates back to at least 1565.

1857, from Urdu khaki, lit. “dusty,” from khak “dust,” from Persian. First introduced in uniforms of British cavalry in India (the Guide Corps, 1846); widely adopted for camouflage purposes in the Boer Wars (1899-1902).

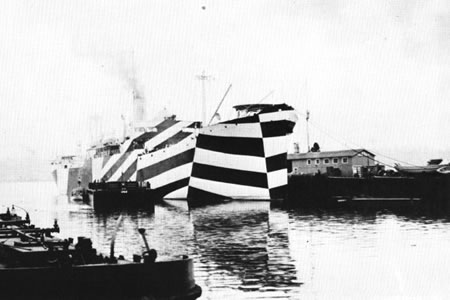

The American freighter, Agawam, 1918

Some references, dazzle, worth exploring — first off, the WWI explorations. As Strider notes “During the first world war the German U boats were hounding Allied war ships all across the seas. In these desperate times the Allied commanders looked towards the art galleries of Europe for inspiration. Thus the warrior and the artistic spirits came together to give rise to dazzle camouflage.”

The USS Mahomet

This came from the specific method of siting vessels on the high seas, using a split scope modeling for telescopic gunnery viewing of the horizon. Uboats utilized sighting, distance and motion as the calculation for torpedoing British vessels: “target a ship it would be pretty far away. Since the ship would not be a stationary target the U boat commander would have to aim somewhere in front of the target vessel. This naturally involved making an estimate about the speed and bearing of the ship. Thus anything that could disguise the speed and direction of the ship would prove of great value in order to save the ships. If the estimate was incorrect the torpedo would miss.”

Sighting scheme for split screen measurement

Seemingly, during the time that the “dazzle” painting concept was in play — along with the ill-equipped siting telescope method — it worked. But what I find fascinating is about the concept of the angularity of the camouflage – it’s not, well, anything that you’d imagine as actually working. In fact, it’s pretty far out there. More like art, it’s been defined as even having been created as just that – by artists of the 20th century, and the man that is credited with their applicable design.

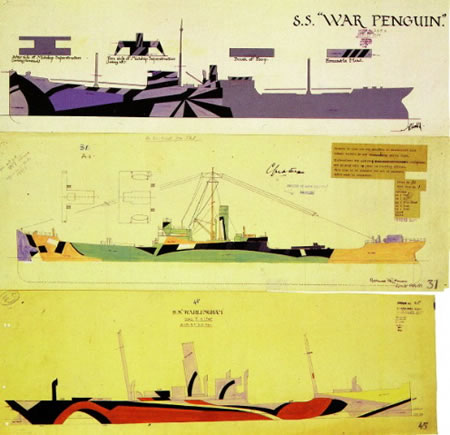

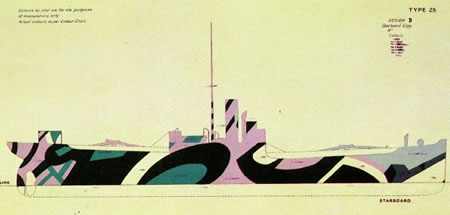

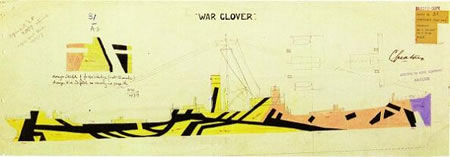

Dazzle painting schemes

According to Conservapadia, Great Britain depended on convoys of ships carrying supplies and war material from North America; normally painted in “haze gray.” However, the ships were striking on the horizon, due to the constantly changing color environment of sea and sky. They were frequent targets of attack by surface raiders, warships, and the new submarine.

A variety of proposals to camouflage ships at sea, blending into the background, were met with disappointment because it was impossible to make the “disappearance” occur. The designer in strategy — British naval officer and artist Norman Wilkinson — suggested a different approach: each ship would be painted in bold geometric patterns, shapes, and colors; the idea being to break up the pattern of the ship itself, and confuse the range finders on enemy warships as to the vessel’s heading, speed, and direction.

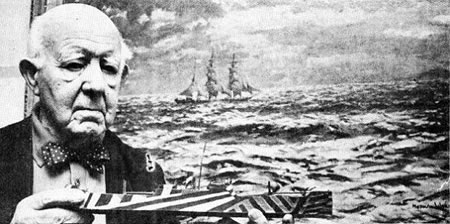

The Father of Dazzle Camouflage Norman Wilkinson

“What followed was, for all intents and purposes, a “nightmare” of design. The ships themselves became the largest canvas of modern art; SS Leviathan, an American troop transport (and former German luxury liner) became a garish pattern of saw-toothed edges and curves; French cruiser Gloire became a horizontal assemblage of zebra-striping (some troop liners painted a silhouette of a smaller vessel, such as a destroyer, on the side against a grey background, to make submarine captains shoot at something else or aim at a smaller target.). So effective was dazzle painting that sinkings dropped, and at one point the captain of a destroyer sent to escort Leviathan across the Atlantic was so confused by the coloration that he had to circle the ship three times in order to determine the direction she was headed.

A sequence of sketches, prototypes and colorations offers the expression of their marvelous conception.

What fascinates is the inventiveness of these treatments, but more so, to the notion of the art of camouflage — what is concealment, the rendering of invisibility in the substrate background of experience.

A grouping of camou-patterning — the brands of camouflage:

Imagery from Phil Patton

One person has authored a compendium of these studies – literally, the design of camouflage, that can be found in this downloadable overview. The concept of concealment might be something to ponder in the nature of dissipation of the obvious — it’s a contrast; or conversely, it’s more about a kind of visual buzzing that confuses the perception of what’s being seen. It’s not a casual observation, however — there’s a tremendous amount of content out there that reaches to the space of defining the nature of camouflage.

More patterning, draperies and garments — the patterning of what can’t be seen:

While these, above, might be less than interesting, it’s an opening foray into the notion of patterning — literally, walking and shooting what I found. Digging in, the nature and complexity of the design principles becomes increasingly remarkable.

As usual, thinking of this as a quick, gestural blog has failed to the curiosity that draws me in deeper and deeper, till I realize there’s a lot more homework to do. To wit, a simple overview on one book that’s built an entire industry around the nature of camou:

DPM: Disruptive Pattern Material

AN ENCYLOPEDIA OF CAMOUFLAGE:

NATURE, MILITARY, CULTURE

DPM Ltd., 2 volumes, 2004. 720 + 224 pp., over 5000 colour illus., £100.00 cloth. ISBN 0 95443404 0 X.

As its title suggests, DPM is an encyclopaedic two-volume work on the origins and use of camouflage in natural, military and cultural contexts. The title refers to the British Army’s standard camouflage textile design fabric or ‘disruptive pattern material’. This unique production was conceived and directed by a fashion designer. Hardy Blechman, who is photographed in green camouflage and face-paint floating neck-deep in a river in Peru, is best known for his Maharishi (Sanskrit for ‘visionary’) label and innovative streetwear designs, such as the popular 1990s ‘Snopants,’ bonsai camouflage and dragon embroideries. The publication of this book was timed to coincide with the launch of his London dphmi store, which sells clothing, toys, uniforms, artwork and camouflage fabrics. As an art book, DPM is as collectible as many of the other items for sale. The two hardcover tomes are beautifully designed and presented in a slipcase. They feature amusing extras such as camouflage origami paper with a design for peace cranes and a cardboard DPM pattern viewer.

Others, to design and art, speak:

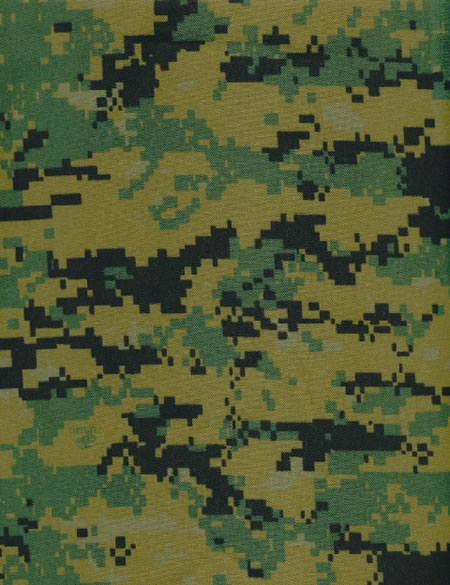

This idea of dazzlement — confusion — is at the heart of a reinterpretation of visual evanescence: disappearing from sight. Phil Patton, a design historian and writer for varying design and automotive publications, offers some added insights and assessment — deepening the gaze into things that vanish in front of our eyes. He notes that, while the impressions might be superficially about blending in, it might be just as much about “standing out. Camouflage hides shapes by generating hints of many other possible shapes. Instead of staying silent, in other words, camouflage succeeds by being noisy: it hides signal with noise. Socially and esthetically, too, camouflage is more and more often about advertising allegiance.” There are varying patterns, and some are very specialized, even restricted, for example — the Marine MARPAT patterning, “tiny anti-copying devices protect it from unscrupulous army-navy store vendors) and the Corps website proclaims that the virtues of the new look seem to imply its very appearance will make enemies run away: “Distinctive to the Marines, the uniform is designed to inspire fear in the hearts and minds of all enemies.” But isn’t the uniform supposed to make Marines invisible?”

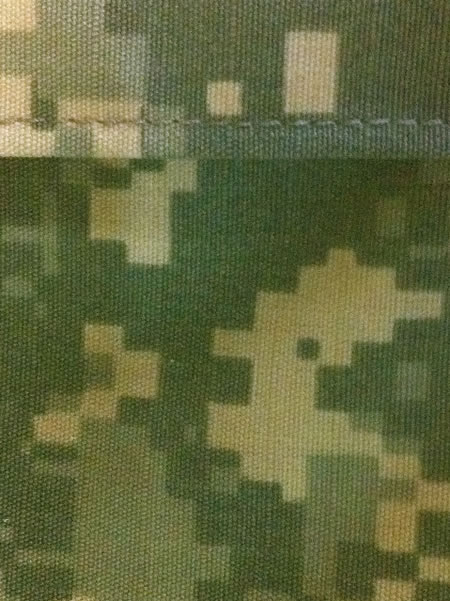

The concept of concealment resolved in the “pixelation is less a result of the way the camo works than of its design and production. From a distance, the edges blur. What is revealing is that the army version of the pixelated pattern is different from the Marine one. The Army is said not to need black since its job is more general, and the theaters where it may be called on to perform are more diverse. But in Iraq the two services fight side by side.”

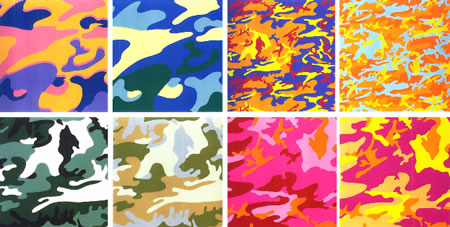

Andy Warhol’s “Camouflage Suite,” 1987

There are variants — wandering the aisles of military stores, the “Army got pixels instead of blobs, which are so, well, Gulf War I. The old “camel-shit” pebble and boulder look of the Schwartzkopf era seems downright venerable now. The new camo is all of a style with the pixelations of video sat phones and blur-outs to protect faces and name bars. “Pixelation” is to the current run of wars what “night vision” was to Gulf War I”—the stylistic keynote, according to Patton’s analyses.

Indeed, the art of camouflage is about the designer / camoufleur — and there’s money to be made on the proposition of creating stealthy patterning – a kind of brand patterning of concealment. To each their own — “style—and art. Camouflage attracts modernists raised to believe that ornament is crime,” according to Patton’s research. With its pattern has a job to do, “artists and fashion designers have long experimented with camouflage. Many used bright fluorescent colors instead of dull natural ones. Andy Warhol’s camouflage portraits, done late in his life, employed this strategy. (One recurrent fashion joke about camouflage is the perennial camo bikini, a play on concealment and revelation.)”

Andy Warhol “Joseph Beuys”

There are superstars of camou design: Bill Jordan of Realtree, “a camo realist” has licensed his patterns to some 800 companies. as well as a business alliance with NASCAR, producing items that show leafy patterns topped with dramatically shaded race car numbers.

Jordan, according to his website,

“By the mid 1980s, the modern camouflage revolution was just beginning. Bill was one of the first to join the market.

He believed that overlaying a leaf pattern on a vertical bark pattern would produce a three-dimensional effect that would blend well with hardwood trees. So, using paper and colored pencils, Bill sat in his parents’ yard and sketched the bark of one of the big oak trees growing there. That tree, which still stands today, served as the inspiration for the entire Realtree line.

After a few false starts and some trying times in the late 1980s, Realtree grew quickly throughout the 1990s, becoming a household name in the hunting industry. Bill has never stopped innovating. He and his company, Jordan Outdoor Enterprises, Ltd., stay at the forefront of the latest developments in fabric design and printing in order to advise customers (licensees who pay a royalty fee to use the camo patterns) about the best ways to maintain quality and performance.

Today’s camo designs are created using sophisticated computers, digital cameras, and photo-realistic printing, and Bill continues to oversee the entire process of creating and launching each new camouflage pattern.

In the late 1980s, Bill began to realize the value of television and video for reinforcing his brand and selling his camouflage patterns.

There are “theaters” of war and there are theaters of locality — the regional influences of concealment patterning favored by hunters are “extremely specific to terrain and season: winter branch or autumn leaf.”

Mossy Oak (also established in 1986 and based in Mississippi), offers a range that are entirely designed — poetically, one might presume wit “realistic limbs and ghostly shadows,” drawn by a local artist based on “a very large and special tree in South Alabama.” Mossy Oak Obsession, originate by founder Toxey Haas, developed using computer images — evidenced here, seasonally flavored:

Plus other concealments:

While some might be artful, others are serious mathematicians in the building of their visual dissolution systems, like the team at HyperStealth. The story goes, laden with camouspeak “in 2002 Guy Cramer, President/CEO of HyperStealth and the inventor of the Passive Negative Ion Generator, began to develop new military camouflage based on mathematical fractals (feedback loops) taking camouflage into an area of science that had been proposed by the experts but none were able to design.

In 2003 Guy Cramer, was commissioned by King Abdullah II of Jordan to develop a digital camouflage pattern that surpassed current U.S. issued uniforms. The King has approved this KA2 pattern for Jordanian Armed Forces and Police. 390,000 uniforms have since been manufactured for Jordan.

In 2005, HyperStealth Corp., began to manufacture military uniforms with the Cramer’s fractal patterns. The company is currently prototyping a uniform with Cramer’s Passive Negative Ion Generator into the manufactured uniforms for Military Forces only. This concept includes notions of improving troop alertness, endurance, balance and reaction time.

In late 2005 Cramer completed the conversion of over 150 traditional (analog) camouflage patterns into 1st and 2nd generation digital camouflage with the pixelated look of MARPAT/CADPAT/ARPAT. These patterns, such as British DPM, U.S. Woodland, German Flectarn, were among those patterns converted. Other patterns included just about every NATO country, Russian and east European camouflage, Australian, South East Asia, the Middle East, Africa. They also converted camouflage from the 1930’s-Present, including a number of commercial hunting patterns, experimental patterns, five different generic forms of Tiger Stripe, Multicam and even improved on the existing CADPAT/MARPAT/ARPAT digital patterns providing a more effective macro element (using larger disruption regions). The Analog to Digital Camouflage Conversion (ADC2) project began in late 2004 and originally was planned to last a few years, but rapid algorithm advances accelerated the Phase 1 completion date to October 2005. Cramer/O’Neill have agreed to license a number of these patterns to HyperStealth Biotechnology Corp. to begin marketing the patterns to different countries and commercial markets.

Cramer has developed over 8,000 patterns which are all under international copyright.

The idea of dazzlement suggests something that stands out, dazzling in the brilliance of a light that blinds, and so too the positioning of the camoufleur — creating something that is seen, and blends what is seen — in scene — and vanishes in distraction. In terms of design, it’s a fascinating proposition, in the very least, drawn from natural principles of design patterning (which I’ve not even addressed) in the concealment of presence, hidden in the absence of aligning sight to recognition.

Dazzle, to reference, comes from “daze.”

Speaking of which — camou or dazzlement — Jeff Koons take:

What, to design principles? Designing camouflage in the natural world is about adapting perceptive patterning — perceptions of arrays of color, form and arrangement — that dissolve the boundaries of differentiation into a blur of similar gestures of structured dissimulation. The notion of cloaking — the shading of deception — creates a masking of the guise of mimicry, veiling and gathering up perceptive alignments and dissolving them into visual chatter.

Tim

––––

Exploring brand innovation workshops:

Girvin BrandQuest®

the reels:http://www.youtube.com/user/GIRVIN888

girvin blogs:

http://blog.girvin.com/

https://tim.girvin.com/index.php

girvin profiles and communities:

TED: http://www.ted.com/index.php/profiles/view/id/825

Behance: http://www.behance.net/GIRVIN-Branding

Flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tgirvin/

Google: http://www.google.com/profiles/timgirvin

LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/timgirvin

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/people/Tim-Girvin/644114347

Facebook Page: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Seattle-WA/GIRVIN/91069489624

Twitter: http://twitter.com/tgirvin