Forging Authentic Brand stories: Examples, Challenges and Directions

If telling the truth becomes questioned in a branding proposition, then how to right the equation?

With Louis Vuitton (LVMH) as a client, we’ve spent a lot of time studying the brand — in the larger context of their holdings (Benefit Cosmetics, for example) and how the larger strategy of the brand plays out to a tiered arrangement of assets.

There is a relatively simple approach in play, and it comes from the top. According to the principles of Bernard Arnault, the foundations rest in acknowledging heritage, supporting the creative and brand story of the brand, and boosting the creative power of the teams that produce the product, advancing wherever possible profits and return on investment. That’s been a wild ride, and I won’t go into the details of the ups and downs of how the evolution of the LVMH assets came into being. Messaging from the LVMH site offers a promise in the mission of their corporate stakeholders — speaking to the larger holdings.

The key promise of the LVMH group is to represent — to their take — the most refined qualities of Western, so-called “Art de Vivre” internationally. To continue their sense of advancement of the brands, LVMH continues to be synonymous with both elegance and creativity, matching acquisitions in alignment with this strategy. “Our products, and the cultural values they embody, blend tradition and innovation, and kindle dream and fantasy.” They’ve formulated five priorities to reflect the fundamental values embraced by all Group stakeholders:

– Be creative and innovate

– Aim for product excellence

– Bolster the image of our brands with passionate

determination

– Act as entrepreneurs

– Strive to be the best in all we do

Group companies are determined — based on the propositions of LVMH luxury brand management — to nurture and grow their creative resources. Working in Paris, the idea of LVMH having their own program at ESSEC, that I once was a guest speaker at, the classic notions of French authority on the nature of the craft of luxury products and experiences, are about allowing freedom, managed within the constraints of operational and distribution tactics. “Their long-term success is rooted in a combination of artistic creativity and technological innovation: they have always been and always will be creators.”

These principles extend in the consideration of “their ability to attract the best creative talents, to empower them to create leading-edge designs is the lifeblood of our Group.” This layering is all a part of the formula that’s passed from Bernard Arnault, LVMH CEO, downways into the heart of the working organization. Extending that thinking, “the same goes for technological innovation. The success of the companies’ new products – particularly in cosmetics – rests squarely with research & development teams.”

This dualistic equation and value – creativity/innovation – is a priority for all the LVMH companies. It is the foundation of their brand strategy and the presumptions of their continued success. Even given these pronouncements there are logistical challenges that have been said to undermine the credibility of the organization and the outward reaches to the media community.

The challenge is the truth. As brands grow, it’s a difficult proposition to manage the right measure of authentic legacy with renewed innovation coupled with the selfsame principles of their initiation. Louis Vuitton, for example, is one brand that is founded on the premise of luxury french craftsmanship. There’s some recollection to note. Two years back, in the beginnings of the global crisis of luxury — and pretty much everything else — we wrote, about the intermixed challenges of authenticity, manufacture and the luxury sector, to the words of Christian Louboutin, (PPR) “Luxury is not consumerism.” “Luxury,” says Christian, “is the possibility to stay close to your customers, and do things that you know they will love.” Christian is at the forefront of “a renaissance of independent luxury houses that offer traditional quality and personal service.” He comments: “I see these men who build luxury brands to make money and I am in the same industry but I feel nothing in common with them.” He is talking, of course, about “Prada, Gucci, Giorgio Armani, Hermes and Chanel, all of which have revenue in excess of $1 billion a year.”

Reveries.com dials in: “Not to mention “LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton, a $11 billion conglomerate whose labels also include Dior, Fendi and Berlutti.” All told, such merchants of “luxury” represent “a $157 (closer to $200 now) billion-a-year mass market whose products now lack the exclusivity — and in many cases the quality craftsmanship — that formed the basis for their cachet in the first place.” As author Dana Thomas writes: “Luxury was a natural and expected element of upper-class life, like belonging to the right clubs or having the right surname. And it was produced in small quantities — often made to order — for an extremely limited and truly elite clientele.”

Dana Thomas infers in her research — that the “luxury business that once catered to the wealthy elite has gone mass-market and the effects that democratization has had on the way ordinary people shop today, as conspicuous consumption and wretched excess have spread around the world. Labels, once discreetly stitched into couture clothes, have become logos adorning everything from baseball hats to supersized gold chains. Perfumes, once dreamed up by designers with an idea about a particular scent, are now concocted from briefs written by marketing executives brandishing polls and surveys and sales figures.” [Thomas, Dana. Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster]

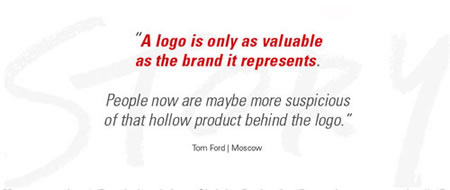

The quote from Tom Ford, in a talk that he gave in Moscow, for the International Herald Tribune’s Luxury Summit there, speaks to content, value, intention and truth in reflectivity behind brands. That it is one thing to have a “logo”; it’s another to have something meaning full, behind it.

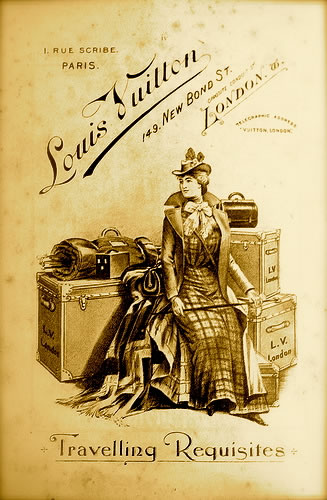

High-profile luxury brands like Louis Vuitton, Hermès and Cartier were founded in the 18th or 19th centuries by artisans dedicated to creating beautiful, finely made wares for the royal court in France and later, with the fall of the monarchy, for European aristocrats and prominent American families. Luxury remained, writes Ms. Thomas, “a domain of the wealthy and the famous” until “the Youthquake of the 1960s” pulled down social barriers and overthrew elitism. It would remain out of style “until a new and financially powerful demographic — the unmarried female executive — emerged in the 1980s.”

And with that renewed vigor in the market for luxury — authentically authored objects of distinction — the strategies for truth devolved. As both disposable income and credit-card debt soared in industrialized nations, “the middle class became the target of luxury vendors, who poured money into provocative advertising campaigns and courted movie stars and celebrities as style icons. In order to maximize profits, many corporations looked for ways to cut corners: they began to use cheaper materials, outsource production to developing nations (while falsely claiming that their goods were made in Western Europe) and replace hand craftsmanship with assembly-line production. Classic goods meant to last for years gave way, increasingly, to trendy items with a short shelf life; cheaper lines (featuring lower-priced items like T-shirts and cosmetic cases) were introduced as well.”

Dana Thomas further summarizes that “The luxury industry has changed the way people dress,” she writes. “It has realigned our economic class system. It has changed the way we interact with others. It has become part of our social fabric. To achieve this, it has sacrificed its integrity, undermined its products, tarnished its history and hoodwinked its consumers. In order to make luxury ‘accessible,’ tycoons have stripped away all that has made it special.

“Luxury has lost its luster.” That closure — a couple of years back. But it continues. As she’s pointed out, that legacy led to continued expansion — brands raised their prices exponentially: the average luxury brand handbag is marked up 10 to 12 times its production cost; clothing as much as 20 times, sometimes more.

The strategy evolved — “they shifted the focus of the advertising from the product itself to the logo stamped on it, thus changing the reason consumers buy fashion, from what it is to what it represents.” To Thomas’ take, CEO Bernard Arnault, head of Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-LVMH, a publicly traded group of more than 50 luxury brands, was named by Forbes to be the seventh richest man in the world but it’s all changed couple of years.

There are straightening factors emerging — during these challenges — “after nearly two decades of getting fleeced, the middle market consumer has wised up and stopped buying.” This challenge has been evidenced in part, because the recession has curbed unnecessary spending, and consumers rightly see fashion — particularly luxury fashion — as ephemeral and unnecessary. There’s a bigger backlash — “consumers have taken a good look at what they are getting — massed produced clothes and accessories, often shoddily made, for thousands of dollars — and realized that as the prices have increased, the quality has decreased. According to luxury entrepreneur, Tom Ford, “It’s junk, and it’s getting junkier all the time,” he told Dana Thomas.

The advancing equation is in the imbalance of expectation — “greed has killed the fashion industry, just like it killed the automobile industry, the banking industry, the music industry and all the others. The key ring to this challenge relates to values — and the idea of newly balancing expectation in relationship to a rethinking. A holistic sense of integrity in the renewed heart of the brand — the principle of value and access, the balance will be renewed.

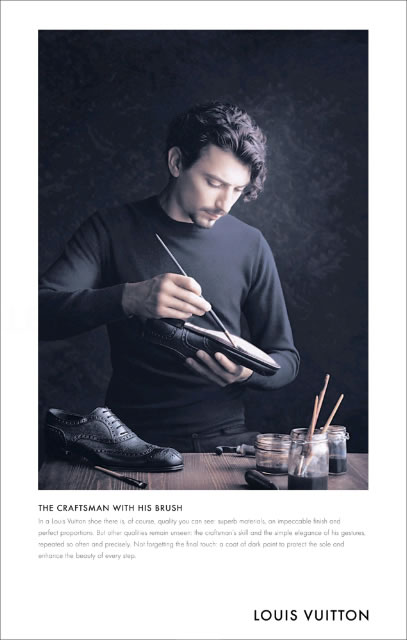

As noted in the Daily Mail, earlier this year, this challenge came to a new reckoning. “With its handbags selling for thousands, Louis Vuitton has built its reputation on the highest quality. But advertising watchdogs have found the French design house guilty of misleading customers with two advertisements depicting its ‘craftsmen’ – because the bags are not actually made by hand. Despite ads showing a ‘seamstress with linen thread’ and boasting of ‘infinite patience’, bags bearing the trademark pattern of an interwoven ‘L’ and ‘V’ are predominantly created by machine.”

Louis Vuitton told the ASA that its “artisans were trained over many years to be able to carry out the various activities involved in the creation of one of their accessories.” Louis Vuitton leadership said the models in the photos were ‘instructed’ how to pose by experts; the fashion house admitted that sewing machines were used as they made the items “more secure and (were) necessary for strength, accuracy and durability.” The issue comes back to the issue of truthfulness.

But Advertising Standards Agency leadership alleged that Louis Vuitton were in breach of the truthfulness clause, saying it “considered that consumers would interpret the image of a woman using a needle and thread to stitch the handle of a bag in the ad to mean that Louis Vuitton bags were hand-stitched.” The advertising also featuring a wallet being made would lead people to believe it was almost entirely hand-crafted. It’s certain that there is some craftsmanship involved in the making of their products, but it comes back to the start — values, message, story, integrity. Being authentic, moving back to the founding principles of the mission will concrete that proposition. What to do? Find a new path to articulating that premise. The ads are gone.

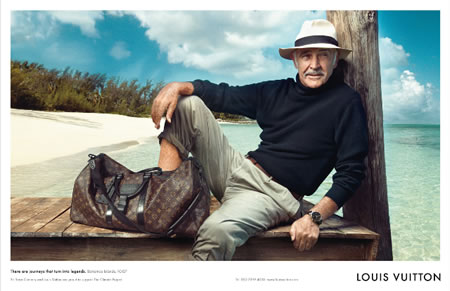

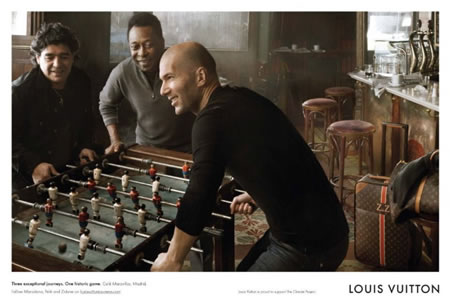

One point, the story. Vuitton has a legacy — it’s been building on that proposition for awhile. This string, from Francis and Sofia Coppola, to Keith Richards, a string of astronauts, Pele and Gorbachev — it laid out something, something identifiable — an element that stretches from the highest, to the lowest — it’s aspirational and comprehensible. The wonder of travel, adventure, pleasure in finding a home on the road, comfort in excursion — that’s the core, and the values of an earlier proposition of messaging the heritage and value of Louis Vuitton’s storytelling.

And in the strategic evolution, bridging from a challenging scenario of authentic truthfulness and representation — and misrepresentation — there’s been another leap. Back to the story, the humanity — and the human brand — lying in the presence of two figures that would suggest another tier of star-filled endorsement.

Smart.

Bono Vox, appearing alone with his wife, Ali Hewson.

It’s a compelling bridge — the first time ever that the U2 founder has appeared in an ad without his performing partners. Significantly, it’s the premier for advertising by Vuitton that doesn’t feature their fashion label. There’s a story to how this evolution occurred — and transforming it just might be. Antoine Arnault, Vuitton’s director of communications, referenced that Edun’s presence in a Vuitton campaign would give the small brand an added boost, empower Vuitton’s renewed commitment — and Edun mission –– to eradicate poverty through sustainable enterprise in Africa garnering international exposure.

“When they go to Africa, they don’t go to see the beautiful landscapes: They’re there to help people,” Arnault said, emphasizing the Edun ethos of trade, not aid. “Theirs is a for-profit company.” According to WWD, A major U2 groupie during his teen years, Arnault said he was surprised to recently have Bono in the passenger seat of his car as they drove out to Asnières on the outskirts of Paris, where Vuitton has its museum and a leather goods workshop. Stopped at a red light en route, a woman spotted the rock star and activist behind the smoked windows, tapped on the glass and when Bono extended his hand to greet her, she kissed it, saying, “Thank you for everything you’ve done,” Arnault marveled.” Some might proffer that Edun’s had challenges in moving merchandise has been part of the problem, but it’s a audience boon to both parties it might be surmised.

Hewson and Bono are wearing Edun, the ethical clothing label they founded in 2005 to advance African trade, supported with a nearly 50% stake by Louis Vuitton. Hewson carries a handbag jointly created by Edun and Vuitton. There’s an added detail in a special separately sold charm, made in Africa.

Breaking mid September, the Annie Liebovitz imagery of Bono and Hewson (video) crossing under the wing of a savannah jumper, landing in South African terrain — positioned with the headline “Every journey began in Africa” The collaboration also will dovetailed with an event during Paris Fashion Week, unveiling Vuitton’s | Edun collaboration “Africa Rising,” an exhibition of contemporary African art, as well as Edun’s spring 2011 collection.

Bono and Hewson donated their fees to appear in the campaign to TechnoServe, a nongovernmental organization that fosters enterprise in the developing world; as well as the Conservation Cotton Initiative, supporting sustainable farming in Africa, and Chernobyl Children’s Project International. Proceeds from sales of the co-designed, hold-all bag, in a patterned embossed, monogram leather, will go to TechnoServe and the Cotton Initiative.

The Africa Rising exhibition is scheduled to open Oct. 5 and run until Oct. 17 opposite Vuitton’s headquarters on the Rue du Pont-Neuf in Paris. The point will be whether the entire package supports the premise of renewal, perhaps a return to story, to the legacy of travel — the heritage of the brand; merging that story with one that has profound humanitarian character might just do that.

Tim | Vancouver, British Columbia

––––

LUXURY BRAND DEVELOPMENT

GIRVIN LUX:BLOGS | https://www.girvin.com/blog/?s=LUXURY

the reels: http://www.youtube.com/user/GIRVIN888

girvin blogs:

http://blog.girvin.com/

https://tim.girvin.com/index.php

girvin profiles and communities:

TED: http://www.ted.com/index.php/profiles/view/id/825

Behance: http://www.behance.net/GIRVIN-Branding

Flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tgirvin/

Google: http://www.google.com/profiles/timgirvin

LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/timgirvin

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/people/Tim-Girvin/644114347

Facebook Page: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Seattle-WA/GIRVIN/91069489624

Twitter: http://twitter.com/tgirvin