I’ve been looking for truth. I’m looking for truth in my self — what do I do, in practicing what I tell, preach, to others. And telling the truth in the reign of the firm — what we do, what we offer, and how we go about doing it, in finding the truth and the heart of brands.

I’m looking for True Brands.

What I seek is:

A story.

A person.

An offering.

Integrity in the making.

Care fullness — in the distribution.

And a legacy that continues.

Here are three opening examples of True Brands:

Harrods

‘Everything for Everybody Everywhere’

Archives | Harrods.com

The Beginnings

The doors officially opened in 1849, Harrods has always prided itself on a “reputation for excellence, that nothing is too much trouble to our customers — finding the finest-quality merchandise.” The store is substantially more than a shopping destination, more than just a splendid building. The Harrods’ story is inextricably linked to the people who have passed through its doors, worked there, written about it and added to its magnificent architecture and brand presence.

Archives | Harrods.com

Noël Coward, Sigmund Freud, Oscar Wilde, Queen Mary, AA Milne and Pierce Brosnan have each added their own mark to the store’s rich patina – and as each year goes on, Harrods continues to grow, adapt, reassess and reinvent itself to create a new history. A story continues to emerge.

Archives | Harrods.com

The Harrods story started in 1834 in London’s East End, when founder Charles Henry Harrod set up as a wholesale grocer in Stepney, with a special interest in tea, then in 1849, to escape the filth of the inner city – and capitalise on trade to the Great Exhibition of 1851 in nearby Hyde Park – Harrod took over a small shop in the new district of Knightsbridge on the site of the current store. Opening with a single room employing two assistants and a messenger boy, Harrods’ son Charles Digby built up the business into a thriving store selling medicines, perfumes, stationery, fruit and vegetables, with added business growth — he expanded the enterprise into the adjoining buildings, employing 100 staff by 1880. But the store’s booming fortunes changed in 1883, when it burnt to the ground in early December; with true Harrods mettle, Charles Digby fulfilled all the Christmas deliveries – and made a record profit for the store. A new building immediately rose from the ashes, and soon it extended credit for the first time to its best customers – among them Oscar Wilde and legendary actresses Lilly Langtry and Ellen Terry.

Archives | Harrods.com

In the early 1900s, the store made yachts to order, ran its own funeral service (embalming Sigmund Freud), sold aeroplanes and built houses. In the 1930s, customers could see one of the world’s first television sets at Harrods or hire a fully equipped ambulance – complete with a nurse. You could join the store’s lending library during the 1940s and even have the clocks in your home wound by the store’s specialist winding service.

Evolution, trend, advancement and change

The 1920s saw luxury apartments on the second and third floors converted to selling space, while the following decade saw south side of the store was rebuilt to provide a sleek vast area of men’s tailoring requirements, as well as a Younger Set Gown Department to cater for changing women’s fashions. The war would change society – and Harrods with it. The store’s lavish tea dances hosted by Victor Sylvester, limousine hire and debutante fashion for coming parties would be swept aside to engage martial austerities. Instead, the store turned to the war effort, producing uniforms, parachutes and parts for Lancaster bombers, and sections of the building were taken over by the Royal Navy. Harrods suffered – there was not much money to be spent during the frugal post-war years. In 1959, the House of Fraser group acquired the store, and began to upgrade what was seen as an old-fashioned institution.

Archives | Harrods.com

Even with Fraser sponsored renovations during the 1980s, Harrods found itself feeling outmoded. The Al Fayed family acquired the House of Fraser Group for £615 million that Harrods became a family-owned firm once again and the store’s fortunes began to turn. Mohamed Al Fayed assumed the title of Chairman and instantly inititated a £300 million refurbishment plan to restore Harrods to its former glory.

Renovations and evolutions under Al Fayed’s design development (Design Director: Dawn Clark AIA LEED AP)

Fayed’s master plan included opening up the lower ground floor to contemporary men’s fashion, a new floor devoted to sports, lavish marble-clad rooms of luxury accessories and a massive, computerized Distribution Centre to support accelerated shipments, topped with the grand masterpiece — the Egyptian Escalator, a magnificent homage to ancient Egypt, designed with expert consulting for authenticity from the British Museum.

Human brand: Harrods

Harrods is very much a city within a city. Covering 4.5 acres, with over 1 million square feet of selling space, the store generates 70% of its own electricity from its own generators, draws water from its three artesian wells. These attributes merely beckon to the legacy — and the care spent on the brand itself — that strides ahead through good times, and bad. There are other crucial attributes — and that’s the presence of the person. In the founding of the brand — there are stewards and visionaries, and while there’s been breach in the heritage with Fraser’s intervention, Fayed’s renewed leadership has catalyzed the vision of Harrods regaining, if not regaling, its legacy as London’s premier retail outlet — now continuously for over 155 years — coupled with the unquestioned, fundamental ethic of selling quality merchandise and giving customers exemplary service. At Harrods, as they’ve marketed — “truly anything is possible.”

Kiehl’s Since 1851, Inc.

“Love what you do, put your heart into it and it will be rewarded.”

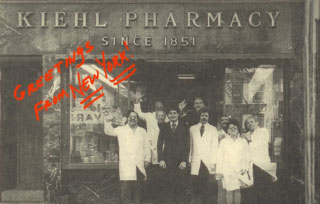

Founded and based in New York City, Kiehl’s Since 1851, Inc. has been built up by three generations of the Morse family, following the formula that made Kiehl’s products chic and the original store a tourist attraction. The company’s East Village address is the site of a 19th-century apothecary, which is crammed with curiosities, from a wunderkammer of family photographs to pictures of Olympic skiers and fighter airplanes, as well as a collection of vintage motorcycles.

Despite minimal spending on marketing, Kiehl’s has garnered an untold amount of favorable press, mostly the result of unsolicited testimonials from New York’s celebrity makeup artists and hairdressers — an ever expanding community of warm, trusting relationships.

Kiehl’s (like Harrod’s) is willing to lavish extraordinary attention upon individual customers, as well as its eagerness to give out free samples. Nearly generic in imagery, in a hand-crafted character, even though expensive, Kiehl’s products are simply packaged, another enduring tradition of the business rather than a current affectation of minimalist brand imagery.

Long before the competitive milieu, Kiehl’s was producing its several hundred natural products without the use of animal testing — exemplifying their brand character in idiosyncratic names as Tea Tree Oil Body Cleanser, Pineapple Papaya Facial Scrub, and French Rosewater Facial Toner.

The Legacy

Before the Morse family created a line of hair and skin care products, its East Village location was home to John Kiehl. In 1851 he established a small neighborhood apothecary, the 1800s version of a drugstore where common compounds as well as more exotic nostrums were prepared onsite. Kiehl sold virility creams, baldness cures, and even a product called Money Drawing Oil. The Morse family connection to Kiehl’s began in the years before World War I, when a Russian Jewish family named Moskovitz immigrated to the United States and adopted the surname Morse. A young son named Irving then found work as an apprentice at Kiehl’s later earning a pharmacology degree from Columbia University. In 1921 he bought Kiehl’s, transforming it into a modern, full-scale pharmacy while also adding homeopathic cures and herbal remedies from the old country.

In 1923, Aaron Morse was born. He would also study pharmacology at the Columbia School of Pharmacy, leaving early to join the army as a pilot during World War II. During the 1950s he became active in helping his father run Kiehl’s and by 1961, the same year his daughter Jami was born, he decided to concentrate on Kiehl’s and took over control of the family business.

Given the attentive character of the brand personality — and the leadership connected with it, Kiehl’s soon took on the personality of Aaron Morse. During the 1960s he phased out the pharmacy and the homeopathic products, developing and selling the natural care products that would make Kiehl’s famous. A wide array of products were formulated, then mixed by hand and packaged on the premises. Aaron Morse disfavored fancy and expensive packaging, preferring generic containers, to which he affixed simple handwritten labels, crammed with as much information as possible, assigning imaginative, if not slightly eccentric names to his products, such as Castille Grapefruit Bath and Shower Soapy Liquid Cleanser. It was Aaron Morse who created the Kiehl’s policy of giving out large amounts of free samples. It was less of a business policy than it was a reflection of the man. He was simply more engaged in making a friend — opening a relationship — than a sale, in pursuing a personal ethic than a profit.

Years before American corporations made a point of instituting “visions and values” programs and formulating mission statements, Aaron Morse created “The Mission of Kiehl,” writing:

“A worthwhile firm must have a purpose for its existence. Not only the everyday work-a-day purpose to earn a just profit, but beyond that, to improve in some way the quality of the community to which it is committed. Each firm–as should each person–contributes to those around it; and by dint of its day-to-day efforts, the message it thereby imparts is a revelation of the quality standard at which its life’s work is conducted.”

In 1983 Aaron Morse told Women’s Wear Daily, there’s something in the heart of the brand that goes beyond conventional commerce.

“Beauty, quality, health and education are what Kiehl’s is about.”

And there’s the added dimension in the deepening of the human presence — in addition to being idealistic, Aaron Morse was charmingly eccentric. His strategies on brand experience might be defined as innovative and ahead of their time: “he believed that his customers should be influenced by a visit to Kiehl’s, which allowed him an opportunity to educate by sharing his enthusiasm for pet interests. He provided a small library with books that included a copy of Gray’s Anatomy (and kept a skeleton handy for ready reference) as well as a book on World War II bombers. He expanded the store in order to create a makeshift museum where, among other objects, he would display part of his motorcycle and car collection. He brought in a xylophone and timpani, for use by himself as well as customers. He might have the public address system play an opera or Ella Fitzgerald or patriotic music”, according to an overview by FundingUniverse.com.

The shop’s museum-like character was also decorated with the old-fashioned apothecary bottles of his essential oil collection, photographs of airplanes and Olympic skiers, and other ephemera, all of which aroused the curiosity of customers and provided an opening for Aaron Morse to engage in conversation. The shop manifested personality — infused by Morse’s peculiar curiosity; he claimed to be an expert on any number of subjects, and was equally eager to discuss the workings of the human body as he was the engine of a car or a motorcycle.

Kiehl’s exotic furnishings, especially its cars and planes, had the added benefit of keeping men amused while women shopped. As with his store’s hodgepodge décor, he was less ahead of his time than he was simply true to his own personality. And that personality is embraced, with committed relationships around the globe.

Aaron Morse’s commitment to the brand was simply not in growing Kiehl’s as large as possible, valuing instead the ties between his products and his customers. For years he declined offers to sell to major department stores, finally relenting in 1975 when Nieman Marcus in Beverly Hills became the first account. Even then, it was more personal than business, his tennis partner was the CEO of Neiman Marcus. New York’s upscale Barney’s account with Kiehl’s, again about friendship, with owner Barney Pressman.

Passage and transition

Aaron Morse convinced his daughter Jami, his only child, to begin the process of taking over the business — because her elementary school was close to Kiehl’s she often stopped by on her way home and became fascinated with the operation. Recalling the early years in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, she said:

“Coming into it, I didn’t imagine that it would be as challenging as it was. It was hard to get my decisions accepted and respected. I wanted to make a brochure of all the products. My father thought it was a waste of money. Any little decision like that could become a power struggle. We’re screamers, and we used to have notorious shouting sessions.”

Still, in the contexts of reflectivity the $1 million marketing budget was essentially limited to samples, which were gaining additional distribution in charity gift bags, a practice in keeping with her father’s commitment to giving back to the community. The essential character here is the relationship between the construct of giving, and giving back — the retail reflectivity of brand relational attitude and personal experience.

Products were no longer produced onsite, and although manufacturing was moved to a facility in Hackensack, New Jersey, products continued to be mixed by hand in the traditional way, albeit in larger quantities. Even lipstick, Kiehl’s only cosmetic, was hand poured and flamed. Jami expanded the company’s mail-order business and added department store accounts: Bergdorf Goodman, Saks Fifth Avenue, as well as Harvey Nichols in England. Despite her familial arguments for marketing action and tools, and fights with her father over expansion, she very much shared his vision for Kiehl’s. She was perhaps even more adamant about giving away samples, going so far as to periodically check on Kiehl’s department store accounts to make sure that sales personnel were giving away enough products and spending enough time with customers.

She retained the simple packaging and the East Village storefront, devoting individual attention to customers in much the same way her father had. Like her father she relied on instinct over formal business planning, and believed in personal attention to detail. She wrote all of the company newsletters and dealt with every piece of mail.

After Nicoletta’s birth, Jami and Klaus moved to Los Angeles; they continued to manage Kiehl’s despite the need for constant returns to New York to address even the smallest issues. The company thrived, with earnings improving at a steady rate and expanding product proliferation to exclusive hair salons and department stores throughout the world.

While little had really changed with the Kiehl’s approach to business, the rest of the world seemed to catch up to it in the 1990s. The East Village location was more in vogue than ever. The unusual interior of the store, the natural products, the lack of advertising, even the refusal to cater to the beauty press, made Kiehl’s all but irresistible to the trendy set — it’s all part of the story.

While its popularity grew by word of mouth, Kiehl’s gained further recognition from a broad range of celebrities–models, actresses, singers, and stylists–who influenced the press from around the world to write glowingly about the company. The exclusivity and mystique of Kiehl’s was a marketer’s dream.

During the holiday season of 1999 Kiehl’s received a great deal of press attention, resulting in an overwhelming demand for its products. The mail-order division had particular trouble in dealing with the increased volume and Kiehl’s, which prided itself on the personal touch, now found itself unable to ship its products in a timely fashion or even to match the right note cards with the right recipients.

Evolutions and challenges

New products that were due to be introduced simply could not find room on the factory’s production schedule. Jami and Klaus had already discussed the possibility of cutting back, but now discovered that they could not terminate department store contracts, nor could they control the demand for their products. Jami now she came to the conclusion that Kiehl’s could not survive in its present condition. The business either had to grow — dramatically — to the next level or it would erode under the weight of demand, and the highly personalized relationship with customers that set it apart from competitors would soon collapse. Logistical resources, far more so than money, would resolve the mounting problems with Kiehl’s.

The sale of Kiehl’s

Long coveted, and offers from corporate suitors advanced — but all presentments were rejected. In February 2000, Jami Morse approached Philip Shearer, president of Cosmair Inc., the U.S. luxury products subsidiary of L’Oréal. While its competitors were acquiring a number of other specialty companies, Cosmair selectively had been studying Kiehl’s — and targeted only them. They quietly pursued Jami Morse for over two years before she called. According to a Fortune interview, she said that Shearer “seemed to be genuinely interested in Kiehl’s. There was clear attention to the details — what would make for the hallmark of a successful transition. “He knew what we were doing; he’d read my newsletters; he knew the ingredients in particular products. I thought he understood who I was and what I was trying to do with Kiehl’s”, according to Jami Morse.

No matter how much L’Oréal paid, however, it insisted that it would allow Kiehl’s to conduct business as it always had, with the clear intent of reassuring customers, many of whom expressed concern about the future of the company. Jami Morse and her husband, were retained as co-presidents of Kiehl’s. Michele Taylor, a marketing executive from Lancôme, a L’Oréal make-up and skin care products company, was hired to serve as general manager. At the end of January 2001, Taylor took over as president after Jami Morse and her husband resigned, although they remained as advisors.

Under Taylor’s leadership, Kiehl’s functioned much the same as before. Taylor even took over the desk used by Irving and Aaron Morse in order to derive inspiration. She focused on transitions that involved the enlargement of the company’s infrastructure, which allowed Kiehl’s to not only meet demand but to enable the introduction of products that Jami Morse had been unable to launch. Kiehl’s flagship store in Manhattan, however, appeared sacrosanct. L’Oréal intended, wisely, to maintain the store in its current condition, it pledged not to reproduce it as the company began to open new outlets around the world. In 2001 a second Kiehl’s location opened in San Francisco, housed in a Victorian townhouse that management felt was in keeping with the Kiehl’s sensibility. Other store openings followed, including the company’s first L.A. area store, in Santa Monica, in August 2002. Clearly, the Kiehl’s mystique was a very valuable property for L’Oréal, and the parent company appeared very much committed to maintaining it. There are continuing keys to the character of True Brands — it’s about the person, the vision, the acumen to spread the cult and culture — and finally, to grow the story of that visioning.

Ferrari

Aerodynamics are for people who can’t build engines.

Times are good at Ferrari. A series of record-breaking sales years and a World Championship title from last year’s Formula 1 season have continued to strengthen the Italian automaker — and pump money into its bulging coffers.

Yet, to the lessons of beauty in authenticity, this brand group carries on traditions that are inherently genetic to the legacy of the founder’s focus on extreme quality, remarkably sustained creativity and passionate commitment to speed and superlative design.

The integral machine starts with the man, Enzo Ferrari.

Enzo Ferrari | human brand

Born in Modena, Enzo Ferrari grew up with little education but was captivated by strong desire to race cars. At the opening of World War I he was a mule-ferrier in the Italian Army. His father, Alfredo, died in 1916 as a result of a widespread Italian flu outbreak. Ferrari became ill as well and was consequently discharged from Italian service. Upon returning home he found that the family firm had collapsed and without other job prospects he sought unsuccessfully first to find work at FIAT — eventually settling for a job at a small car production group called CMN, directing the redesigning of used truck bodies into small passenger cars. He took up racing in 1919 on the CMN team, but had little initial opening success.

In 1920, he enlisted at Alfa Romeo, racing their cars in local races with more successful outcomes. In 1923, racing in Ravenna, he acquired the Prancing Horse badge which decorated the fuselage of Francesco Baracca’s (Italy’s leading flying ace of WWI) SPAD fighter, given from his mother, and taken from the wreckage of the plane after his mysterious death.

This icon would have to wait until 1932 to be displayed on a racing car. In 1924 he won the Coppa Acerbo at Pescara. His successes in local races encouraged Alfa to offer him a chance of much more prestigious competition — Ferrari turned this opportunity down and did not race again until 1927. He continued to work directly for Alfa Romeo until 1929 before starting Scuderia Ferrari as the racing team for Alfa.

Ferrari managed the development of the factory Alfa cars, and built up a team of over forty drivers, including Giuseppe Campari and Tazio Nuvolari. Ferrari himself continued racing until the birth of his first son, Alfredo Ferrari, in 1932.

Alfa Romeo’s support lasted until 1933 when financial constraints made Alfa withdraw. Only at the intervention of Pirelli did Ferrari receive any cars at all. However, despite the quality of the Scuderia drivers the company won few victories Auto Union and Mercedes dominated the era. With a demotion in employment at Alfa, Ferrari left the company.

The Beginnings

Building anew, he set up Auto-Avio Costruzioni, a company supplying parts to other racing teams. Like so many others (like Harrods, noted above) during World War II his firm was involved in war production and following bombing relocated from Modena to Maranello.

Entry to the Ferrari founders compound

After World War II, Ferrari sought to shed his political positioning — renew his reputation and make cars bearing his name, founding Ferrari S.p.A. in 1947.

Ferrari Racing Galleria

Ferrari participated in the Formula 1 World Championship since its introduction in 1950 but the first significant victory was not until the British Grand Prix of 1951. Emerging success followed in the first championship in 1952–53, when the Formula One season was raced with Formula Two cars. The company also sold production sports cars in order to finance the racing endeavours not only in Grand Prix but also in events such as the Mille Miglia and Le Mans. Always focusing on speed and stamina, many of the firm’s greatest victories came at Le Mans (14 victories, including six in a row 1960–65) rather than in Grand Prix.

Enzo Ferrari’s Villa and Racing Team Guest Quarters

In the 1960s, the problems of reduced demand and inadequate financing forced Ferrari to allow Fiat to take a stake in the company. The company became joint-stock and Fiat took a small share in 1965 and then in 1969 they increased their holding to 50% of the company, later, in 1988, Fiat’s holding was increased to 90%.

Challenges, transitions, passages

As the chief creative visionary, Ferrari remained managing director until 1971, and even after stepping down he remained an influence over the firm until his death. The input of Fiat took some time to have effect, and historically speaking, it might be referenced that — yet again — there’s a challenge with a holding company positioning reigning the financial strings bridging creative sway over the genetic character of the brand legacy.

More challenges emerged — it was not until 1975 with Niki Lauda that the firm won any championships — the skill of the driver and the ability of the engine overcoming the deficiencies of the chassis and aerodynamics. But after those successes and the promise of Jody Scheckter title in 1979, the company’s Formula One championship hopes fell into the flameouts of crashes, failed engines and death. While 1982 opened with a strong car, the 126C2, world-class drivers, and promising results in the early races, Gilles Villeneuve was killed in the 126C2 in May, and teammate Didier Pironi had his career cut short in a violent end over end flip on the misty backstraight at Hockenheim in August. The team would not see championship glory again during Ferrari’s lifetime.

Ferrari Galleria

Enzo Ferrari died on August 14, 1988 in Modena at the age of 90. His death wasn’t made public until two days later, as by Enzo’s request, to compensate late registration of his birth. He died at the beginning of the dominance of the McLaren Honda combination. The only race which McLaren did not win in 1988 was the Italian Grand Prix.

Ferrari Galleria

It was held just weeks after Ferrari’s death, and, fittingly, the result was a 1-2 finish for Ferrari, with Gerhard Berger leading home Michele Alboreto. After Ferrari’s death, the Scuderia Ferrari team has had further success, notably with Michael Schumacher, Rubens Barrichello, Felipe Massa and Kimi Räikkönen from 1996 onwards. He witnessed the launch of one of the greatest road cars Ferrari F40 shortly before his death, which was dedicated as a symbol of his achievements. In 2003 the first car to be named after him was launched in the Enzo Ferrari.

Ferrari Galleria

Among his other successes, he was awarded a Cavaliere del Lavoro in 1952, to add to his honours of Cavaliere and Commendatore in the 1920s, Ferrari also received a number of honorary degrees: the Hammarskjöld Prize in 1962, the Columbus Prize in 1965, and the De Gasperi Award in 1987. In 1994, he was posthumously inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame.

After a legacy of challenges, explorations and inventive successes, a new Ferrari has emerged, during the course of the last decade.

The advance of innovation

Ristorante Aziendale

Ferrari has completed work on two new buildings at its Maranello headquarters that help complete the automaker’s “Formula Uomo” program, launched in 1997.

Ristorante Aziendale

“Formula Uomo” serves to improve the way Ferrari’s headquarters operates in many different aspects. From improvements to the grounds, to increased employee and family services, to saving energy and incorporating environmental awareness, the program’s aim is creating a work environment that harmonizes with employee needs.

With regard to environmental protection and energy saving, Ferrari CEO Amedeo Felisa introduced the two latest projects embarked upon: a photovoltaic system and a trigeneration plant. He commented: “This emphasis on environmental awareness has also led to the extension of the green areas both inside and outside the company buildings. Thus far we have planted over 1,000 trees along the central boulevard and the streets that open off it.

“The overall objective of this urban planning project is to provide pedestrian walkways and cart routes for production services. Also, a series of shelters will be added soon in which over 100 bikes will be parked for employees to use for moving around the campus.”

“These new energy generations plants,” said Amedeo Felisa, “will allow us to cut the amount of electricity we take from the national grid by 25% and to reduce our CO2 emissions by 35%. ”

“With the addition of these two new buildings,” stressed the President, “we have completed the renovation of the entire Car Production Area that began in the late 1990s, and has involved the investment of over 200 million euro. Next year we will be going one step further when we begin work on the new GES facility.”

Along with the official presentation of the two new buildings, Ferrari’s head officers also announced a series of new services for employees and their families.

Employee Cafeteria | Aziendale

These range from free medical/fitness check-ups for all employees and their children, first and second home loans at competitive rates, personalised loans for family requirements, and discounts on school and university textbooks.

We intend to create a working environment unlike any other anywhere in the world,” says Ferrari President Luca di Montezemolo.

New car assembly line

The presence of the hand

While there is extraordinary technology in play in the new factory compounds — completed in the Summer 2008 — there is the profound presence of the hand. From the very beginning, under the tuning of Enzo’s creative guidance, the car, the engine, the person, the materials — they are entirely “woven” together by the care of the hand.

The Carrozzeria Scaglietti

The Ferrari Textiles Factory Section

The Automotive Finishing Centre

“A working environment where safety and environmental protection coexist in harmony in facilities designed and constructed with the workers’ needs in mind.”

Brent Edwards’ innovation science site comments: “Mario Almondo, head of Ferrari’s HR, discusses how Ferrari has on-site creativity classes outside of business hours that are open to its 3000 employees. These classes explore a variety of topics, but they all relate to creativity: sculpting, photography, writing. The classes usually involve an artist describing their craft and talking how they create and obtain inspiration, with questions from the Ferrari attendees. Sometimes a moderator leads the discussion (Almondo mentions once using a local TV talk show host), and the classes are purposefully kept small to allow interaction between the artist and Ferrari employees.”

How does this deepen the brand intelligence and innovation at Ferrari? “The intent is to nurture creative thinking in their employees and hope that it flows into their work–classes are in Ferrari buildings and not at local schools to create an association between creativity and their jobs.” Almondo, leading the brand innovation implementations for employees, states that

“We want to let the creativity metaphor work at the level of their unconscious.”

The brand presence is felt in the spirit of the products, the cultural management of the organization and in the integration of production and creativity in place.

The buildings achieve highest standards of technical excellence and they have been constructed in a way that considers the well-being of the employees based there. In particular, the focus has been on providing functional work environments, solutions that allow optimum air-conditioning, and overall care for energy efficiency.

For this purpose, innovations in building cladding, in the development of a special aluminium profile to support the various architectural visions to design an effective bioclimatic structure that guarantees the highest grade of natural lighting and the lowest expenditure of energy.

Ferrari’s facilities include:

* Wind tunnel by Renzo Piano

* Mechanical shop (MDN, Marco Visconti & Partners)

* Technical headquarters (Massimiliano Fuksas)

* Paint shop (MDN, Marco Visconti & Partners)

* Assembly line (Jean Nouvel)

* GES Racing Logistics (Luigi Sturchio)

* Restaurant Aziendale (MDN, Marco Visconti & Partners)

Holistically, the framing is about the thorough integration of brand story — and visible messaging — throughout every aspect of the brand personality — from the cultural intentions, the care of human capital, the innovations and passion about the product evolutions and finally, the recollection of story.

Personally, I like these shoes.

And this bike, too:

What are the outcomes, what’s been learned, what’s the baseline for this definition of True Brands?

• Truth. Things don’t always go the way that one might expect – business is down, bad things emerge, crises happen — but true brands stand for the truth. the heart of the authentic is in being truth full — connected to the soul of the telling. From there, everything springs.

• A story. Stories are layered entities — there are themes that loom large — the big picture; and there are storied elements that are smaller, more delicate. Like any narrative exposure, it’s all in the details and how they are exposed and explored.• A person. Any brand is about a person. It’s about one person connecting with another. It’s about one person creating something to share with another — in reflection.

• An offering. And that’s what it is — something “carried over” — from the Latin, offerre “to present, bestow, bring before”, from ob “to” + ferre “to bring, to carry”. Any brand has an offering that represents a resonant connection.

• Integrity in the making. Integritas, the Latin origin of the word, expresses “soundness, wholeness” — but this extension of experience runs like a thread, a note, that builds a expansive melody of connection to an audience. That ranges from people to product, from message and mission to architectural environment and visible language.

• Care fullness — in the distribution. It’s one thing to create the product — the offering — it’s another to assure that the relationship between the producer and the receiver is seamless and fluent. That might be production, that might be a retail environment, it might be epiphany at shelf.

• A legacy that continues. Authentic brands have truth in their origination, there’s passion and love in their making, but it’s not about the moment. True brands last — they have commitment in their staying power, it’s not a momentary expression, but a long-lasting experience, responding to trend and change, transitions and bringing new evolutions into product intimation — whether service or profession, object or idea.

http://www.harrods.com/harrodsstore/

http://www.kiehls.com/

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/18/fashion/18CRITIC.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

http://musei.ferrari.com/?lang=en#