Developing Hand-crafted Symbols as Deep Metaphors

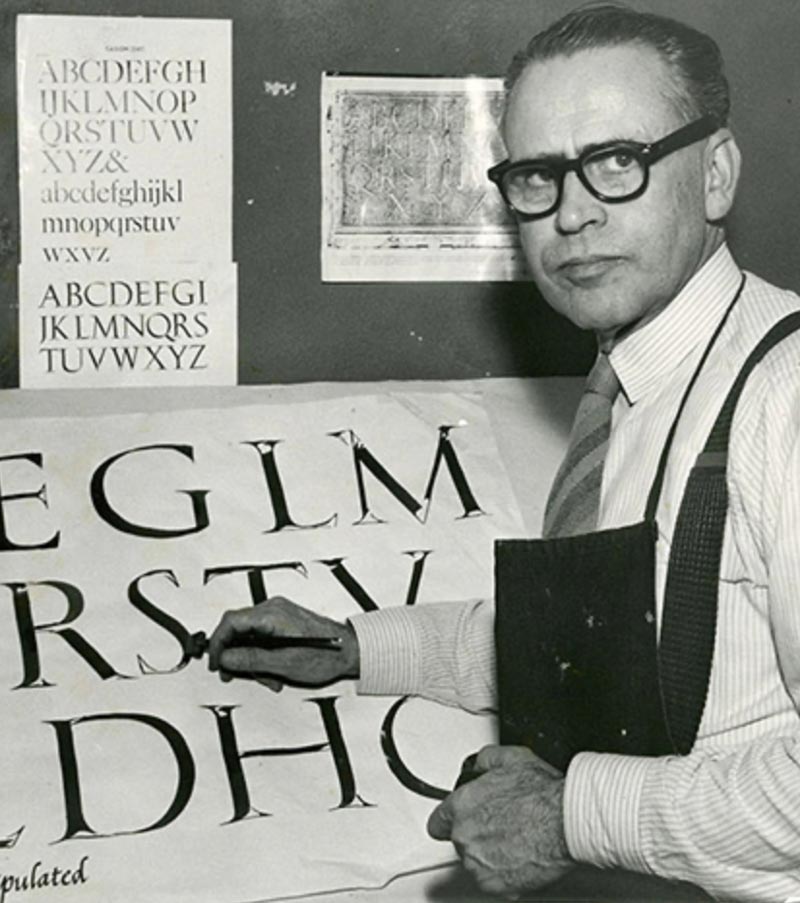

During my college years, I studied calligraphy with Lloyd Reynolds—

the maestro of the calligraphic arts that inflamed Steve Jobs,

during Steve’s limited foray at Reed College. And a core precept—this would be the I + O above, in the strings of weaving an alphabet, any form, any type, its entire mystery lies in the confluence of these two character, the universe of form is there, it is the DNA of any font—the spirit of how these two letters, the secrets of their curves, shall voice the vocabulary of a letter system.

It was during this time—the 70s—that I, too, was hanging out in Lloyd’s house, camping-out on the floor of his library—filled with rare books on design, paleography, art history, typographic design, paper making and book-design / making. And in the workshops at Reed College. Also through Lloyd, I explored and studied the principle of Zen Buddhism and the aesthetics of wabi sabi—and that journey, particularly D.T. Suzuki’s Zen and Japanese Culture which examines the spirit of Japanese experience and the cultural legacy of the Chinese origination of these principles in the 8th century. And they’re transitioning to other parts of Asia, including Japan. Other authors, and I’ve, written about my times with Lloyd, as well as Steve Jobs, and the intertwinements of these artistic, historical, and calligraphic interplays.

The interiors at Ryōan-ji, a temple in Kyoto.

What struck me was the aesthetics of the principles, deployed in art, architecture, swordsmanship and the samurai way, calligraphy, ceramics, tea preparation, simplistically natural foods, and the interiors

in which these aesthetic experiences are manifested.

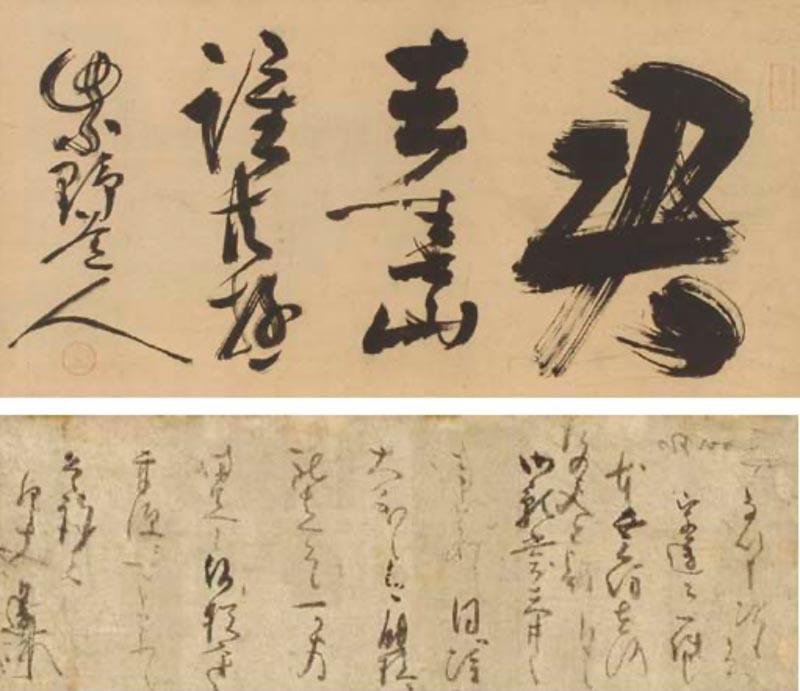

Rhythm, patterning, the fluency of calligraphy, or painting. The observer might comment, it is painting? Or, it’s calligraphy that strokes the power of a narrative, delicately or bluntly illustrating the idea within.

Kogetsu Sogan | the Seven Maxims | 1640

Study with a Zen Master also lends itself to poetic and brush drawn expressions of particular ways of painting—and iconoclastic approaches to teaching, in the parable-like inquiry of the kōan, expositions in writing, and poetry. This forms in delicately framed poetic abstractions, the principle of haiku, the disciplined cadence of a poem that is made on what it doesn’t say, what’s left out, rather than what is written in—at seventeen syllables, three lines at 7 / 5 / 7.

Wait—that’s a garden? Here, a monk raking the symbolic patterning of waves at Ryoan-ji, Kyoto.

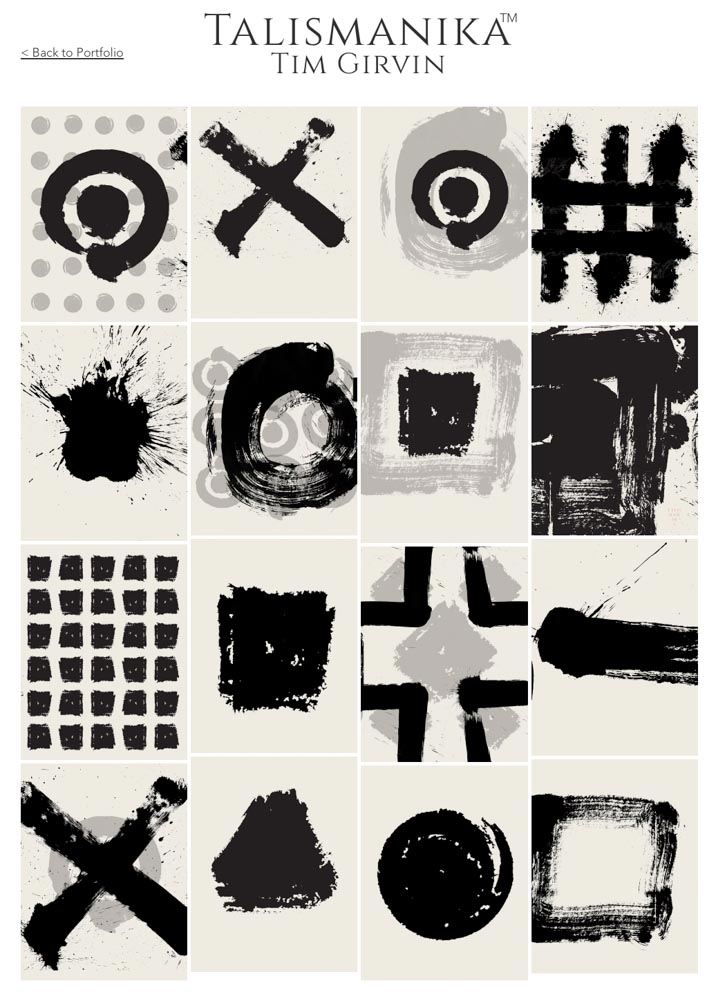

In my work with Lloyd, I explored the idea of taking the precepts of Chinese calligraphy—the energy of the idea—the ch’i, a dynamic flow that could be evidenced in the capture of the expression in energized movement, flow, rhythm—the lightning strike of the brushstrokes and drawn imagery.

It’s not the precise reflection or lifelike representation—it’s literally expressing the life-force of the principle in the narrative. Some earlier Girvin notes on this here. I took these ideas into the notion of brushstroking environments

and furniture—the collection of Talismanika™.

I was curious—where could I take this ideal, expand it to enlarged, built applications?

To go big, I drew large.

Here’s a video of a large circle, a Zen ensō, the ultimate expression of enlightenment. Not implying that I am. Just practicing. This showed up as a series of rings, a circle on a circle, installed.

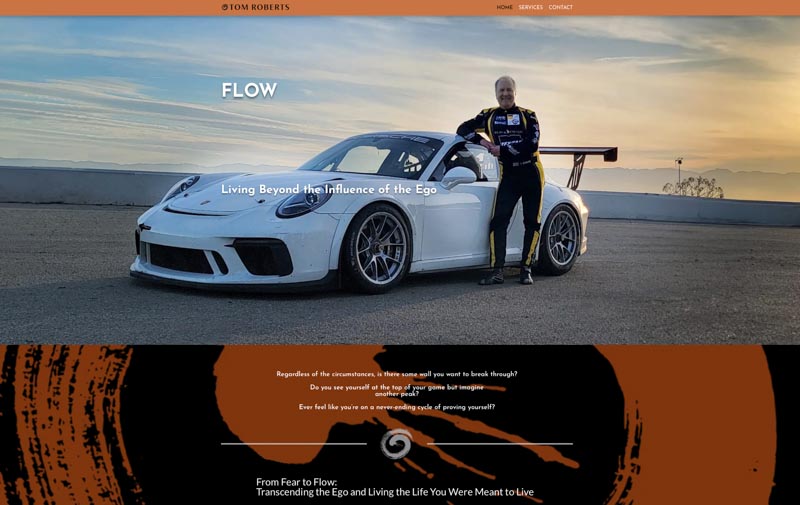

Then I’ve applied this flow-related brush work to brand conceptions—like Tom Roberts, a long-term client

relationship—a Tibetan Buddhist, race car driver, and stunt pilot. In the instance of developing a symbology, he asked—in a string of collaborative explorations, for a representation of flow.

I went to sand.

And water.

And brush.

Stones.

And arrived here.

The concluding point to this exploration lies in considering brands as underlaid by deeper metaphors, symbolic states of mind that incite attraction, captivation and embarkment. Mystical, to its etymology, is the Greek mystes, as “initiate,” as in a less than commonplace ritual—or, pardon the word, “cult.”

Sometimes in the deeper work of brand, the soulful and psychic explorations of meaning, it does feel like one is working in a more spiritual space. One with “brand spirit” surely. And spiritual practices, as we’ve noted, are often reflected in narrative, “what’s the story, who’s telling it, who is the story for, what does it sound and feel like?” And, most crucially, “who cares?”

The telling of the story is part of the magic of the work. And everyone loves a good story that they can believe in, learn from—and perhaps live by as an ongoing inspiration.

Tim

I collaborate

GIRVIN | Strategic Brands

OSEAN | Built Environments

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Follow Us:

Facebook LinkedIn Instagram Behance