True Brands | (2nd in the series)

In some recent branding workshops in White Plains, I’d explored, as an opening exercise for the executive team, the concept of brandstories in the context of personal experience. That is: what brand affected you — presumably as a child, that remains unforgettable in your connection?

Some people in the session talked about the idea of their childhood connections with “outdoor stores”, like — the (then) expeditionary retailer, Abercrombie & Fitch; or others, like the Northwest classic — Recreational Equipment Co-operative (REI); or, others — like Orvis. L. L. Bean, for example. Actually, I found that rather consistent link compelling.

People. Outdoors. Memory. Brands.

There’s something in the power of nature, our connection to it, and the early link to how we might be “clothed in it”, that is, seemingly, unforgettable.

It is a place of memory, our connection with the outdoors — and how we got there. As we’ve first explored our link to nature, there’s been some support there that has bridged our experience. Could be boots, warm coat, backpack, hat, gloves. A protective link that sticks in the mind, and links to that experience.

I was a Boy Scout — and finally, an Eagle Scout, so the range of my childhood is deeply connected to the outdoors. And getting the gear went from Army-Navy Stores, used equipment, camping outfitters, and sometimes — literally, finding gear at discount shops like Goodwill. Later in my life in the mountains, or the outdoors, I moved to equipment that was more “brand consistent” — TheNorthFace. So runs to Mongolia, Tibet, Bhutan, even south east Asia, the mountains of Thailand and the broad plains of Cambodia — and home, the Cascades and Olympics, I kept my gear in that packing place — a NorthFace duffle.

And in a way, the phrasing of this exploratory is focused on brand consistency, memory and personal story — and hopefully, in the context of commerce — the kind of engagement that leads relationships back, and back again.

Trust in truth.

There’s beauty in simple design — honest structuring in fashion design and story. Sure, there are plenty of stories that have been explored here. Fashion and mythic design: http://blog.girvin.com/?p=1028. Or fashion and place-making: http://blog.girvin.com/?p=1450. Retail story merchandising: http://blog.girvin.com/?p=1257.

But this is different — this is about hard brands, true brands, authentic brands, that you might consider going back to. And if you’ve got history and a sense of connection, a return to a brand experience that’s memorable.

According to the NYTimes, Lucky Magazine, Esquire — there’s a connection between the sense of utility — usefulness — long lasting, hard working, defensible clothing and the implications of trend in “longevity”; the exploration of the art of “fashion that the more time you spend following it, the more interested you become in clothes. What sounds like a redundancy is not when you consider that by clothes one means not the hyped-up goods cranked out by the global luxury machine but the work or sportswear that is resolutely immune to vogues and seldom featured in Vogue.” Luxury is one thing — an exaggerated cost for things well made, by hand; craftsmanship in work-person-ship is another.

Guy Trebay continues: “By clothes one means the kind of garments seemingly designed after the architect Louis Sullivan’s famous and overused dictum that “form ever follows function” — that is, if “designed” is not too pompous a term for a plain white T-shirt from Hanes.”

It’s actually about clothing that is so simply honest, so directly functional, that it lasts forever — yet whose designers, the inventors of the brand, might remain forever unknown. “One would have a tough time naming the anonymous genius behind the nearly perfect cotton crew-neck shirt or, for that matter, the person who came up with the auto mechanic jumpsuits, the thermal undershirts, the engineer’s boots, the moccasins and tin cloth jackets and gum boots that so neatly marry form and function that no one has found the need to alter their design for many decades.”

It is in this place that fashion seems to stay on a perpetual tack that inspires the higher lines of design, like Yves Saint Laurent and his “working classism” design evocations, or Calvin Klein’s reflection on the perfection of the 19th century, can’t pull ’em apart, riveted Levi Strauss jeans. They’re perfect. Simple, elegant, bulletproof. They last forever and they get better the longer you wear them.

There are other brands that lend themselves to that space. Like Filson, which is coincidentally, a Northwest brand. Interestingly enough, I used to talk to the owner of Filson — he was in the same building as I, decades ago, on the waterfront next to the Ferry Terminal, on Eliott Bay.

Filson is an outfitter that comes from the era just past the timing that might be defined as “goldrush” — the latter 1800s — and even today, their gear has the hard-working ethos stitched right into it. It’s the only place that I’ve every connected with that actually offers re-waxing of weather repellant clothing.

And, to the character of this exploration, it’s one of the few brands — authentic or otherwise — defines itself on its stories — and by the way, your stories (of you and Filson gear) — C. C. Filson’s Pioneer Alaska Clothing and Blanket Manufacturers to outfit fortune seekers stampeding to Alaska and other points of meteorological bitterness. “He made jackets and blankets, as well as boots and shoes for miners like the one whose diary recorded that even by amplifying the sensation of “the most bitter ice blast that has ever pierced your marrow” a thousand times, one could still scarcely conjure the depth of a springtime chill in the Chilkoot Canyon”, the deep freeze of midwinter on the Yukon.

Kim France, the editor of Lucky, the shopping magazine, and the author, with Andrea Linnett, of the newly published “Lucky Guide to Mastering Any Style”, have a deep respect for authentic classics”. And what one might call an authentic classic might be, instead, something that is authentic to your personal history — your story and how you connect with the legacy of an experience with a product. Like these boots. For me, being in the mountains, they started here — and lasted here, for decades.

An early favorite for me — mountain handlers, Red Wing Boots.

An early 20th century advertisement for Red Wing.

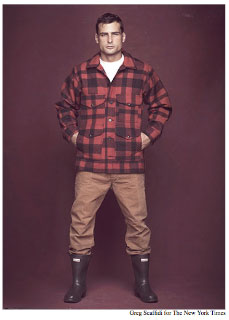

“There are all these great standbys that don’t really have anything to do with the lifestyle we lead here in New York and are totally underappreciated,” she added, referring to things like Red Wing engineer boots, Aran sweaters, Barbour jackets, Sperry Top-Siders, Woolrich jackets, Alden cordovan loafers and Pendleton shirts. And the RedWing clan expands to a grouping of other honest gear that reaches to the same flavor of hard built integrity.

The family includes other working classic staples, like Worx, Irish Setter and Carhartt.

Everything is about work — that crosses over to living.

The Pendleton story, another classically northwestern outfitter reaches back into the truth of what been made to work — hard — from before. To the notion of the brand, the story — indulge this expanded exploration:

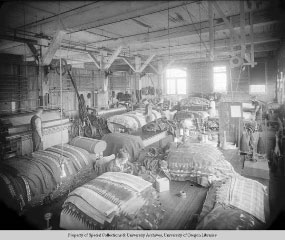

Pendleton, their legacy — 1863, traveling down the Atlantic seaboard, crossing the Isthmus of Panama on a burro, and sailing up the Pacific coast was a grueling four-month passage, Thomas Kay, a young English weaver, it was a dream come true. An old hand at sea voyages, he had already crossed the Atlantic years earlier to work at east coast textile mills. With skills honed, he was now headed to an area with ideal conditions for raising sheep and producing wool — moderate weather and plentiful water, located in America’s newest state, Oregon. From these humble beginnings, Kay’s opening developments, his first mill, rose a dyed-in-the-wool American success story — a solid foundation for what was to become Pendleton Woolen Mills.

As a major railhead serving the Columbia Plateau, the town of Pendleton was a wool shipping center for sheep growers of the region. The mill, originally built in 1893, began as a wool scouring plant, which washed the raw wool before shipping. With transitions in the family — a new legacy emerged, the Bishop leadership heritage.

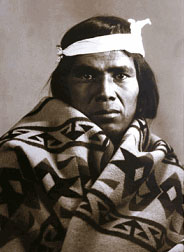

In 1895, the scouring plant was enlarged and converted into a woolen mill which made bed blankets and robes for Native Americans. The production of Indian blankets resumed as the Bishops applied intuitive business concepts for quality products and distinctive styling. A study of the color and design preferences of local and Southwest Native Americans resulted in vivid colors and intricate patterns — from the Nez Perce nation near Pendleton to the Navajo, Hopi and Zuni nations.

These Pendleton blankets were used as basic wearing apparel and as a standard of value for trading and credit among Native Americans — also became prized for ceremonial use. Under the direction of the Bishop family, Pendleton expanded into other areas of woolen manufacturing. In 1912, the addition of a weaving mill in Washougal, Washington, broadened its capability for fabric variety, including suitings — wool shirts for men were largely utility items in the early 20th century, Pendleton evolved and developed the distinctive patterning that largely defines the brand today.

A Pendleton advertisement from the 1960s.

Like Burberry, premium, distinctively patterned, rain gear — a legacy that reaches back into the psyche of early mimetic connections — reborn, in stable utility, today.

Working it: Woolrich and Carhartt

This family thread has continued — now newly hip, honestly made, and characterizing a kind of humble “with it” quality — to produce Pendleton leadership with a legacy of hands-on management for five generations — warranted to be a Pendleton since 1863.

“It’s been a pleasant surprise for me, being from Texas, that some of the things I grew up with, and realized with regret I’d discarded along the way, fearing they would hopelessly reveal the hayseed in me, have come back,” said Jay Fielden, the editor of Men’s Vogue.

Trebay continues: “Anonymous, eminently functional and reasonably priced, the clothes seem perfectly attuned to times like these. That they are cool besides seems to derive not from any sartorial irony or nostalgia for the manual labor fast vanishing from the American landscape or even from a conservative cultural atmosphere. It is more simple than that. They do the job.”

As well, others comment that given the reign of luxury as a form of perfected commerce — yet bedeviled by the ills of mass channeled production, there’s a truth-element that’s bringing us back to basics — well made basics. Thomas Persson, the editor of Acne Paper, “We’ve been in a time of extreme consumerism, and at a certain point, you want to withdraw from the celebrity, flash and razzle,”

“Luxury has changed so much that (true) craftsmanship is what we’re moving toward now. People want to be more subtle and comfortable, and these kinds of traditional items of clothing bring a certain sense of assurance and familiarity.”

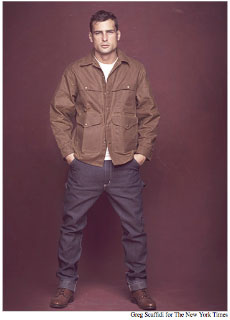

A Filson assemblage, t-shirt and carpenter pants

Bill Kulczycki, the president of Filson, said — “We don’t do things for a season and then drop them; we do things for 50 years” — these anonymous, simply designed and functionally thought-through garments convey another sort of cool, drawn from the ineffable aura of continuity. They last because they need to — they work because, in some instances, you might say that life depends on it.

“Those clothes are always going to look right,” said Ms. Linnett, the Lucky creative director, referring to Filson Mackinaw jackets. “I have a friend who says that when you see those things on someone, you know they know what they’re doing,” she said.

Personally, along with the others in this overview, so thoughtfully orchestrated by Guy Trebay, there’s a return to the truth of things — your clothing — that is well made, designed to last, and legacy producing; it’s your story, as much as the brands that you wear. And in this way, it’s a telling, on a telling — it reaches on one level to the story of the making; and on another, it reaches to the heart of your experience in these that you adventure forth…

What’s your take? Is there any connection to you, to your clothes, and your past? What story, there?

TSG | Decatur Island, San Juan County