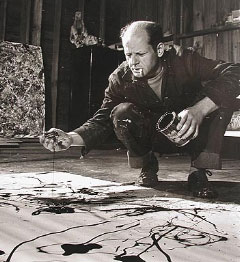

Martha Holmes | Jackson Pollock Time©1949

Steve Lopez and Nathaniel Ayers: exploring concepts of the visual language of creativity, music, madness — and the warmth of humanity in redemption.

“Madness is the salt that keeps good sense from rotting.”

Nikos Kazantzakis

As a younger person, I was captivated by the wildly creative person: the artist. To the wild spatterings of Jackson Pollock, I was mesmerized. And in the swerving drunken character of his life and death, I was smitten.

I was compelled by those whose creativity seemed to border from the manic, to taciturn sobriety to the nearly insanely, perhaps brilliantly, intoxicated. I’d presumed, really, that artists were all like that. Either they were on fire, or — to the contrary — they were slightly morbid, depressed and silently contemplative.

I met all the types in between — as well as those two extremes. And I had some exposure to them in their work, my work, and my earlier exploration of who I was. I met Frank Stella, Guy Anderson, Barbara Schwartz, Jacob Lawrence, Leonard Baskin, Kenneth Callahan, Tony Angell, James Turrell, Dale Chihuly, George Tsutakawa, Elaine DeKooning, Alden Mason — and I learned something, from each, about the work. The passion of it. How hard it is. And where I was going.

Harold Balazs, a spectacularly emotive creative firebrand constantly shook whatever foundations I seemed to have about art, making art, or being an artist. He lived outside Spokane, at Mead — in a studio cul-de-sac, down a long sliding and sandy road, a curling riverlet flowing through the property. There, amazing things would be made. Bronze sculptures. Cast concrete totems, baked porcelain enamel steel panels of brilliantly glassed and gas-fired sand, wood carvings, delicate water colors and screen printed posters and art ephemera. A remarkable human being — he was (and perhaps still is) incessantly hammering into me the idea that art was irrepressibly hard.

According to Harold Balazs, and others: “It was — it is — goddamned hard work.” And no matter how talented I might’ve thought I was, I was destined to work my ass off — forever. That was then, this is now.

In fact, when I’d moved from a career from science to art — he’d told my parents “cut off his hands”. Yes, allegorical, but intimating just that — “art isn’t paradise; it’s focus, hard work, commitment — and you might win, you might be a success — but the proposition in passion is about finding your self.” It’s less about the mere lustration of strategy to design solutions, or painting the right portrait or creating the right rendering.

So when we were asked to work on Paramount Studios’ The Soloist, set to launch in Spring, 2009, it was a recalling of that notion of art, art fullness, and the incipient character of indelibly impassioned, obsessively madness that can drive great creativity. Even driving it, literally, right over the edge.

That is the edge — there is a brink between blindingly bright creative thinking, and its action, that is just that — a delicate balance that just might blur over the edge to madness. It is the nature of art to allow — any of us — to see things differently. That might be the new glimmer of a special light in a painting, to an abstraction that is suggesting the illumination of a whole new way of seeing.

The Soloist tells the true story of Nathaniel Ayers (played by Jamie Foxx), a musical prodigy who developed schizophrenia during his second year at Juilliard School. Ayers became homeless, playing the violin and the cello in the streets of downtown Los Angeles. Robert Downey Jr plays Steve Lopez, a columnist for the Los Angeles Times who developed a friendship while writing an article about Ayers. That article can be found here. LA Times, and, to the positive or the negative, there have been added effects — even blogging from the intra-hood. Dana Goodyear, the author of the New Yorker article on the Lopez | Ayers telling, offers that the scene, has changed dramatically after the filming began — in many ways for good. Yet, perhaps in other reasons, there are challenges and controversyhttp://centralcitye.blogspot.com/2008/04/just-re-reading-i-have-been-re-reading.html.

That’s beside the point of reference to this exploration — which is really about the idea of trying to capture that sense of madness, refracted brilliance and creativity, found in one. And what might be madness in the one, is a renewed sensation for another. That might be the quintessential character of the experience between Lopez and Ayers, in that in one discovering the other — and the interweaving of music (and madness) — there are learnings in experience that transpose each of them. And, for that matter, the story is true.

Truth, be told

When we work, we write. And that writing, thinking about what we do, is almost more poetic than strategic:

What is it about being alone, singing a song that perhaps only we hear? And then, what about that instant when you hear a song that’s been sung alone, played alone, that suddenly comes to life in your mind, your experience? And you are changed. There are layers of transformation here — people that, the two characters, live in the complexity of their own worlds, doing the work that is part of their living. And their songs are their own. But they connect, combine, and there’s a new journey, a new revealing that is empowering a kind of new song. It is, profoundly, the song of the soloist that is in each of us, that can come out anew in a shared experience — that extends from the one, to the other, to the community. Spreading a story that’s magic. Beauty is there, in the whirling worlds of the conflicted, and those that peer in. You look in, and you are brought in. Taking something new out — together — with each other. For each other. For all of us.

This exploratory is about layering. The story is layered, rich patterning — it goes from the split mind of the one, to the spinning and complicated world of another; and it’s about the transforming of both — and the others that are touched — to a new seeking. So these treatments, some of them simple, others complicated — are about the idea on the surface and what lies beneath. There are layers of patterning, from the asphalted graffiti of street art and darkened sub-highway byways, to the brilliant colorations of light — seen anew. There’s a lot of light here — It’s coming through, shining through in the idea(l)s of the cinematic telling. We have built layer on layer on layer — and like the mind, there’s always something easily seen in the scene of the surface, but there is a lurking, lingering, expansion on those tracings and frantic retracings below. In being with schizophrenic people, what happens is a kind of resolute confidence in approach — and you can see that in their drawings and paintings — there’s a sureness. We draw that way, then, in the selfsame-minded style, we go back in. Again. And again. That tracery frames the layering of the mind — split, or not — that’s part of the beauty of the experience. Hard beauty. But it’s there. Lifting you up.

So, in the final form, it’s about gathering the story, listening, moving into the heart of it, then comprehensively illustrating it — moving into the soul of it. And in this, we follow the leadership of our clients — Nancy Goliger and Abbie Wisdom, profoundly connected, spectacularly discerning creative directors of theatrical advertising visioning, at Paramount Studios.

We look for patterning. Like that image above, the color, the texture, the light. These are all components of production design — and this is another layer in the story, it’s part of the design and the process of making a film. And we live in that space, in understanding more of how the film’s identity might appear in the context of titling and marketing imagery.

And there is the content of the writing — the notations — that go along with the compulsive passions of the acutely creative. How might that be integrated in the imagery — or, for that matter, the scrawling spirit of the identity:

In the mind, stories are laid out in writing, and –in the case of how that handwriting looks can reflect the character of the madness — it might be obsessively detailed, illegible, filling every possible space…this, too, informs the character of the realizations.

What is the character of creating a design treatment that lustrates that sense of the one side of madness, another side to brilliance and still another to the nature of redemption?

Titling treatment from the current trailer.

Added explorations:

Still, there are framings of color, to imagery, to match potential campaign thematics. From here, we gather up the stills, and link them to the possibilities in coloration for the theatrical advertising treatments.

What’s your take, on the intimation of madness, art and the mix, in creativity?

Tim Girvin | Hollywood

All images: Copyright © Paramount Studios 2008