SIMPLIFYING THE CONCATENATION OF BEING.

Sometimes, simply being is—just by itself, complicated; it’s trying to be good to oneself, respectful of others, following a plan and a pathway, and doing good. Sometimes, it feels like it’s all a little bit much—then again, in being, it might be necessary. For doing these things is better than NOT doing them, not caring—inattentive, unawares, slothful and ill-committed, inactive or, to that darker, unlit contrary, doing bad.

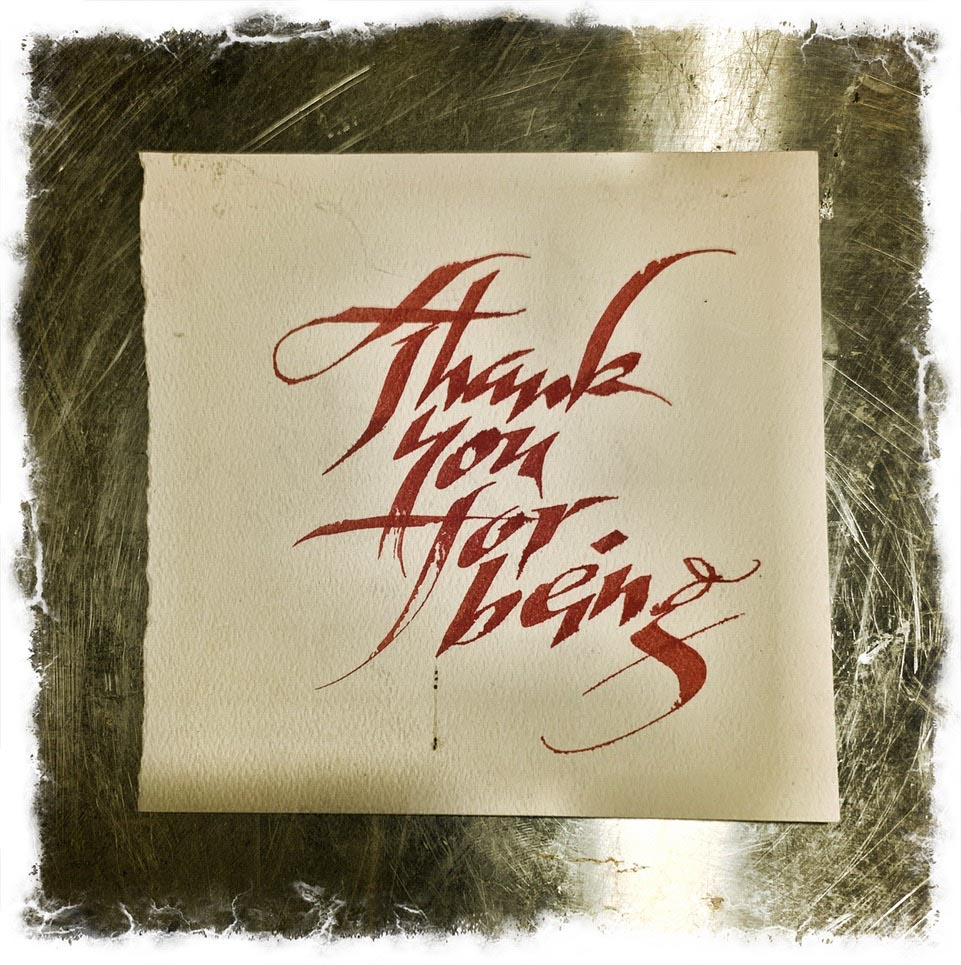

It reminds me of this phrasing, coming from friend Scott Oki.

Sometimes,

thinking of the principles of Cha’n—

as noted in the ideogram below,

it speaks out to meditation and quietude,

silent rigor, discipline and restraint

or Zen—it’s about the decluttering, the untangling of the knots of oneself and getting back to the simple, the more pure basic threads—better to the sheer alignment of simple asks and tasks—and making them into a journey of contemplation of beingness.

I chop wood, then I split it again, then I split it again—each time, it takes more focus and precision—each split becomes riskier. Better to be right here, right inside the task, than to be meandering in the mind about other monkeying.

Focused work is, of course, about finding beauty—

it’s the looking deeper for something evermore beautiful.

And for you, designer and strategist,

that would be simpler, better, leaner, focused.

The principle of being focused isn’t just a proposition of Zen-like clarity of mind, or a distinguished Asian form of engagement, but something which finds its revealing elsewhere.

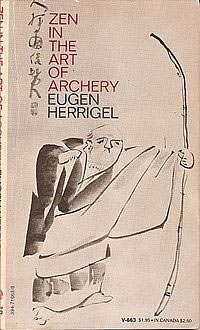

So, for example, in the principles of Japanese Zen principles of archery—”be the target, let there be nothing else.”

The zen approach to archery similarly aligns with the target, the breath, the draw—and in that release of the bowstring—

the target itself, the eye that is the center.

Others say something similar.

“The marksman

hitteth the mark

partly by pulling,

partly by letting go.”

-Egyptian proverb

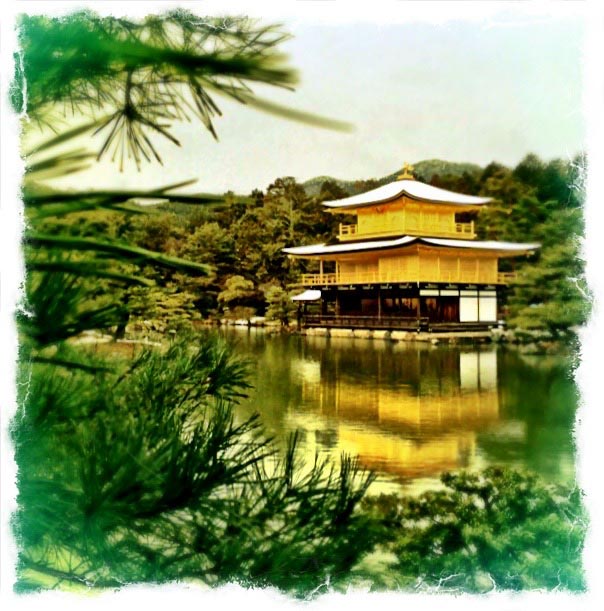

For me, the point of fascination with Zen came from studying the implications of zen-like contemplation characteristics in being in—traveling throughout—Japan. Going into the most austere monastery compounds, there is a plain discipline of design—the simplest of details—doors, walls, compounds, grounds, garden—that look “simple,” yet are profound moves in construction, balance and detailed form-synchronies.

Kyoto and Osaka, Japan—journeying.

For more than 25 years, I’ve been studying zenga.

Specifically, this is contained as a collection is comprised of enso, brush-stroked entities of contemplation and the quest towards satori.

These are the paintings of Zen masters. They are rendered in the haboku style, which is the most captivating, to my aesthetic; this approach to painting is called “broken ink.” It’s about capturing the energy of an idea or subject, layering message inside painting — even comically or whimsically — saying something in nothing. It’s about an empty-handed gesture that means every-thing.

And no-thing.

And, in the tradition of Zen, every thing.

The paintings in the collection are produced somewhere between 50 and 200 years old; and in the meditative practice of painting these, the masters of the monastery or nunnery, the place of practice in the zendo, these are lessons offered.

They paint mostly in black on white,

and the shades of color washed in between.

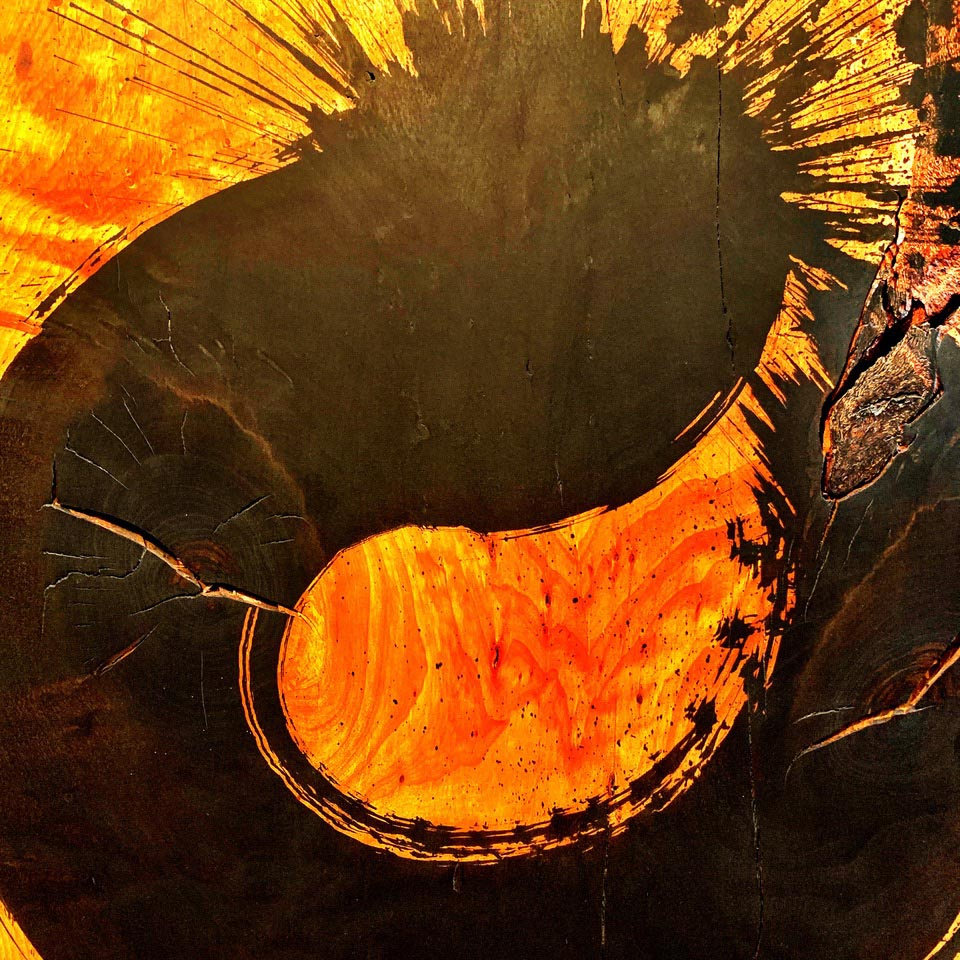

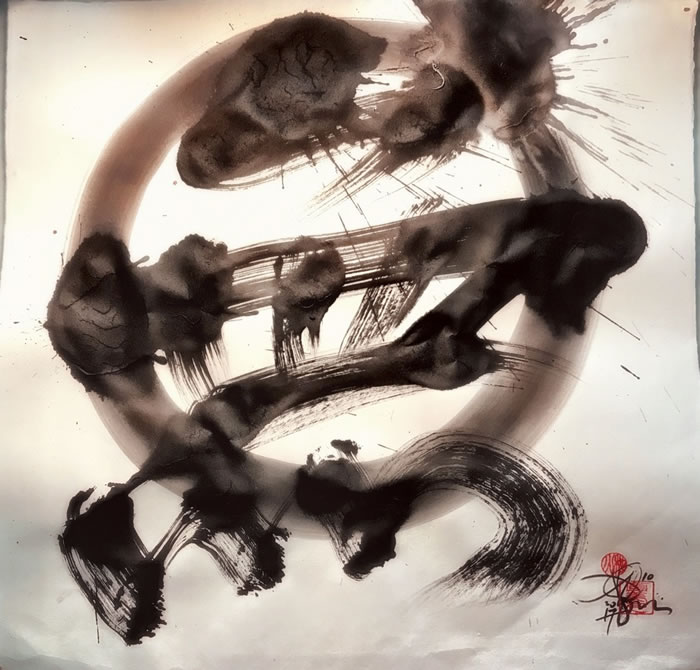

Here is my draft of Muu—the calligraphy of nothingness, examine another storytelling, as you will.

You can see the initiative strokes

and the renderings

on top of the drafts,

the stroke sequence—

the move-in,

closer, then further and further,

until there is

another world, whorled—

a talisman of nothingness.

Whorls in worlds, worlds in whorls.

But the real stroke is not the stroke, but what’s not there. The black drawn line is about the idea—the white is the place around the idea; the abstraction of the simplest notion—the not doing of the Zen practice; it’s about the incessant patience of release. The circle stroke draws the world in, and the universe with out. The circle is the ring of bone,

the brush enlivened,

the spirited circle, the enso.

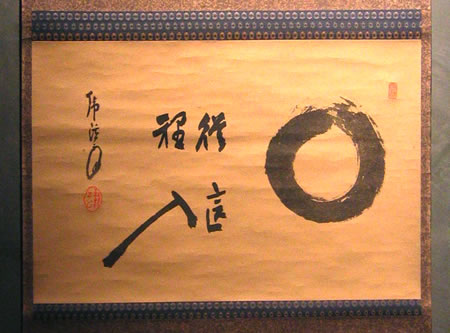

This one, from the GIRVIN Zenga collection, came out of hiding, in a book by Audrey Yoshiko Seo: Enso, Zen Circles of Enlightenment.

Weatherhill, London.

The painting is here:

GIRVIN ZENGA COLLECTION:

Hoshino Taigen (Saishokan) • 1865–1945

“Enter from here.”

Photograph by Deanna Carroll

__

Speaking to practice, meditation, mind fullness…it’s interesting that

the etymological reference of concentration is “with circle.”

It is the center point of contemplation, the center of the circle.

Finally, what this all comes to meaning for me, to brand, design, strategy, is the transformative power of the mark—a stroke of meaning.

For designers, the script of statement, the inscribing of meaning lies in the stroke—what is the mark that you make, in telling a story?

The GIRVIN X:

In the brand visualizations that you create, a mark has meaning.

It’s a reflection of content. The circle, the square, the line—each a vocabulary of statement, a lexicon of scribed perspective—a seeing through, from one realm to another, a carrier of message.

To the seer and experiencer, that could be an unforgettable encounter, and surely that is what we’re all seeking:

unforgettable moments in memory.

To those that are open.

Tim Girvin | OseanGIRVIN

—-

Explore GIRVIN Cloudmind | goo.gl/33c5P8

TEAM-BUILT STRATEGIC INNOVATION WORKSHOPS